The true story of Jerry Krause and the breakup of the Bulls

My 2017 eulogy to the Hall of Fame Bulls GM, reprinted

“The shame of it is that he had mostly been forgiven — and then The Last Dance brought it all back up.”

That’s what my friend Deremy1 told me a few weeks ago, and we weren’t talking about Michael Jordan. We were talking about the late, great Jerry Krause. When the Hall of Fame general manager passed away March 21, 2017, his sendoffs were largely cordial.

Three years later, less than 10 minutes into a 10-hour documentary, with the U.S. locked down at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the entire sports-loving world turned its attention to The Feud: Michael Jordan vs. Jerry Krause.

Suddenly Krause was back in the spotlight and for all the wrong reasons. It was a shame, in my view, that this documentary did not find a way to humanize and even celebrate Krause. If we understood who he was, the documentary would have been even more dramatic and darkly ironic.

But alas, it wasn’t in the cards, and a new generation of basketball fans met “the villain” Jerry Krause, the man who broke up the most beautiful team in sports.

Or did he?

As I explained in my eulogy for Krause published three days after his death, the real story of the breakup of the Bulls isn’t so cut-and-dry. I published my Krause retrospective on BlogABull, but SB Nation and Vox Media recently pulled the plug on the site and the article is gone.

Fortunately, I have it in my files, and while Wayback Machine has it in theirs, I wanted to republish it here so that it can be more easily found. (You should also check out the new BlogABull on Substack!)

So here it is — and I’m adding footnotes with more material.

Best,

Jack

The true story of Jerry Krause and the breakup of the Bulls

By Jack M Silverstein, March 24, 2017

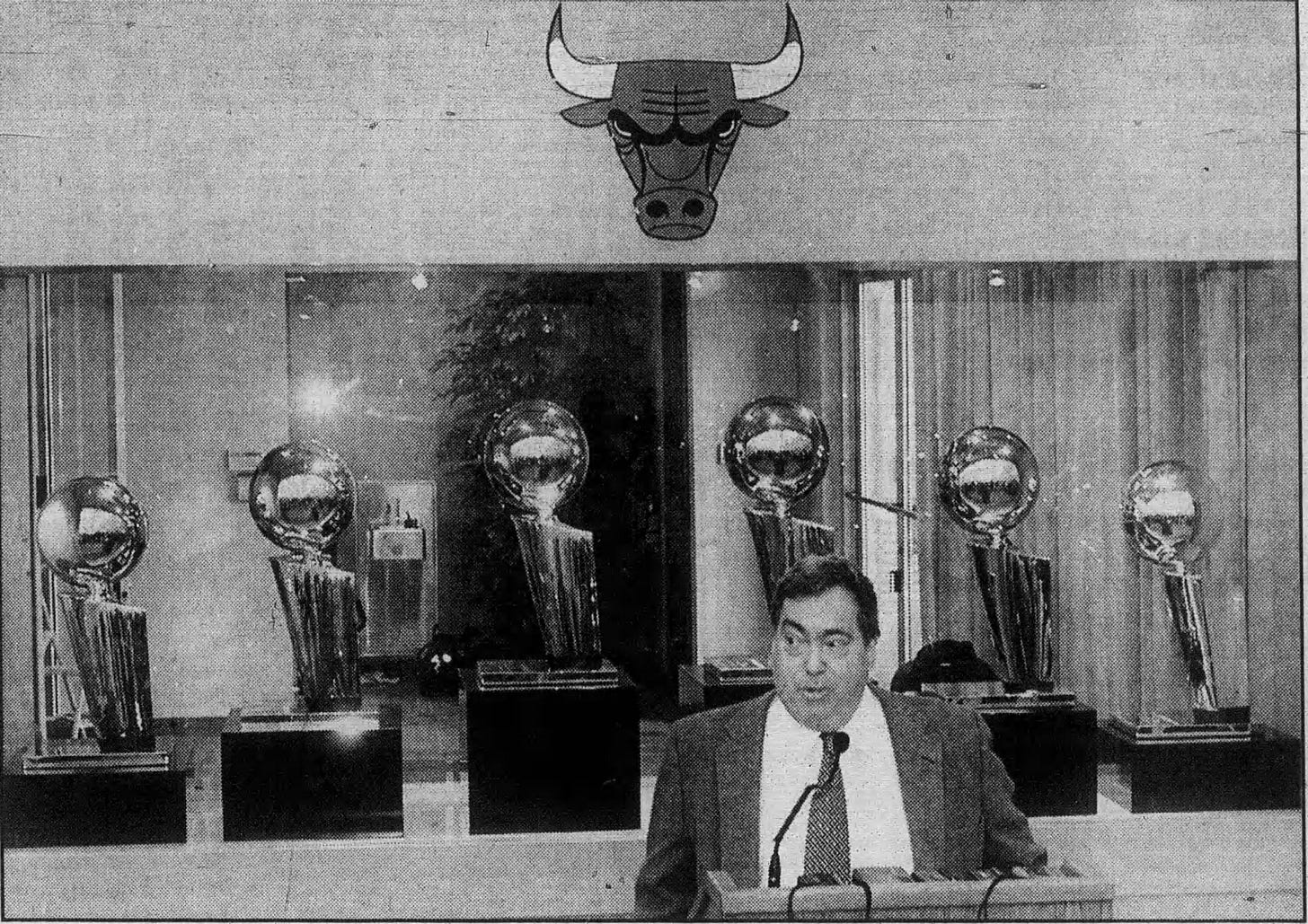

“My job was to win,” Jerry Krause said last month, and though he won six championships with the Bulls there was one battle that now, even in death, threatens to consume him — his never-ending face-off in the history books and sports fan consciousness with the one, the only, Michael Jordan.

You can’t beat Mike. Doesn’t matter who you are. To quote Fight Club, on a long enough timeline, Michael Jordan will beat your ass. It happened to the Pistons. It happened to Magic. It happened to Croatia. It happened to Jewel and Dominick’s.

So there was no way the sloppy, uncouth, overweight, overwrought, overexposed, unsocial Krause was going to win a duel of public opinion against the most popular athlete the world has ever known.

As a result, Krause has become the Yoko Ono of Chicago sports2 — the improper scapegoat for the dissolution of a legendary collective that, in truth, was torn apart internally. Through a twist of cruel fate fueled by sports fan frustration, Krause goes to his grave known as much for his alleged masterminding of the end of the Bulls dynasty as for his actual role in its formation.

Krause is gone now, passing away Tuesday at the age of 77. Beautiful, complimentary tributes continue to pour out, from ex-players on Twitter, including Scottie Pippen, Charles Oakley, and Stacey King; from Phil Jackson and Michael Jordan in interviews and statements; and from the journalists who covered him, most notably Sam Smith, Rick Telander, Cheryl Raye Stout, Mike McGraw, and K.C. Johnson.3

These tributes will help fans fight past the trend of assigning Krause too much blame for the end of the dynasty. Of course, 12 years ago ESPN took the contrarian tack and tried to give him no blame at all, producing a program on Krause for its “Top 5 Reasons You Can’t Blame…” series. The reasons ESPN provided — the reasons “you can’t blame Jerry Krause for the demise of the Bulls” — were the needs and personalities of MJ, Jerry Reinsdorf, Phil Jackson, and Scottie Pippen, plus Krause himself, who apparently because he built the Bulls couldn’t possibly be responsible for their destruction.

The truth, as always, lies in the middle. Jerry Krause played a role in the end of the dynasty. He was not the evil-doing puppet master as popular history might have us believe. Two things can be true at the same time.

This, my friends, is what really happened.

Phil Jackson’s seven-year theory

The reason people blame Krause for the end of the Bulls dynasty — beyond his general unpopularity with players, coaches, fans, and media — comes down to the belief that he forced Phil Jackson out of the organization. Krause pushed out Phil, and Mike was on the record that he wouldn’t return without Phil, and the dominoes fell from there, right?

Kind of.

Yes, Krause made it known during the 1997-98 season that Phil’s time with the Bulls was over. Jackson, Jordan, and Rodman all signed one-year contracts after the 1997 season, meaning those four plus Scottie Pippen all had expiring deals after 1998. Before the ’97-’98 season even started, Phil told Rick Telander that “the Bulls definitely have plans to hire another coach for next year. Probably Tim Floyd of Iowa State.”4

And Michael told Telander later that season: “I won’t play unless it’s for Phil.”

So there is credibility to the domino theory.

But there’s another theory that played a role, and that was Phil Jackson’s theory that a coach loses the attention of his players after seven years. That belief came from Jackson’s father Charles, a traveling Pentecostal minister in the northwest who told Phil when he was young that, “You can only stay in one place five years and then your message starts falling on deaf ears.”

A minister may have gotten five years, but a coach, Jackson felt, got seven. In 1995 — his sixth season as Bulls head coach — Jackson told Krause and Reinsdorf he would only return after his contract expired in 1996 if the team cut loose of every player from the first three-peat, including Pippen.

This would satisfy Jackson in two ways: he would have a new flock, as it were, thus resetting his seven-year theory; and he would have a chance to embrace the challenge of winning without Jordan, something that Krause later wanted to do as well.

This plan was upended when Jordan left baseball because of the strike and returned to the Bulls. (Was this a crafty Reinsdorf maneuver? I’ve always wondered.) The team kept Pippen but unloaded B.J. Armstrong in the 1995 expansion draft and Will Perdue a few months later in a trade for Rodman. Thus Jackson had a whole new roster that he could teach to play championship basketball, and he had Jordan and Pippen to lead those efforts.

Still, by the time the 1997-98 season came around, Phil was entering his ninth season as the team’s head coach. That was two more than his seven-year theory, and we should note that Phil held to this instinct in Los Angeles: he took a one-year hiatus from coaching in 1998-99, coached the Lakers for six seasons, took another one-year hiatus in 2004-05, coached six more seasons, and left again. No matter the relationship with Krause, Jackson was a grown man who made his own decision and needed a break.

“I wanted to coach seven years,” Jackson told Telander. “Now it’s nine. … But this is our last year — we’re playing it out. For Michael, Scottie, Dennis, Steve, Luc, Jud Buechler, a couple others, this is it.”

Michael Jordan’s burnout

In my book about the 1996 Bulls, I laid out my reasons for believing that Michael Jordan’s first retirement and baseball career was on the level, and not a secret suspension as so many would like to believe. Among them was that as early as 1991, as documented in Sam Smith’s The Jordan Rules, Jordan was telling friends and teammates that he wanted to retire. He said it all the way through the 1993 season, even before the intense scrutiny surrounding his gambling, even before his father was killed5.

“I didn’t plan to come back6 (to basketball),” Jordan said before the 1995-96 season. “And in some ways that was probably good, because I fixed my mind away from the game. I totally forgot about the game. And then once I got a taste of it again it was a different kind of taste — a taste that I’d been looking for for so long.”

Michael had basketball fatigue. Minor league baseball erased it. By 1998, it was back.

“You want the real story?” Smith wrote in 2004. “Jordan burned out.”

Jordan, Smith wrote, couldn’t stand playing with Pippen, Rodman, or Longley, and would not return without Jackson. “It’s a bad way to end an unbelievable run,” Jackson recalls Jordan saying about Krause bringing Floyd on board.

Yet as Smith points out, while Krause may have promised Floyd the job, Reinsdorf hadn’t. And Reinsdorf was a man who felt that the only reason to own a sports team was to compete for championships.

“I made the decision,” Reinsdorf said in 1995, as written by Smith in his book Second Coming. “As long as Michael is here we have to try to win and worry about what happens later.”

MJ was driven to win championships. But he could be satiated, and the number that would satiate him was six, one more than Magic Johnson’s five. He told Ron Harper as much after winning the 1996 Finals. After his “last shot” in Salt Lake City in 1998, he seemed determined to keep stacking chips, telling Pippen in the locker room (but kind of just talking into the air) that “they can’t win until we quit.”7

This was typical of Jordan. In the afterglow of a new championship, he always felt he could play forever. He did the same thing in 1993, despite telling teammate Darrell Walker the next night that “I think you’ve just seen the last of me.”

Yet in reality, he knew the time was up.

“It’s why he did pose,” Smith wrote about MJ’s championship-clinching jumper. “He knew that was the last shot, and that's the way people talked about it then.”

Jerry Krause: visionary, scout, antagonizer

What I’ve described so far would fit well enough in the ESPN “Top 5 Reasons” program. Unlike that program, I’m not about to pretend that Krause didn’t also play a role himself in the dynasty’s demise.

At his core, Jerry Krause was a scout. That was his identity. He told Telander and others that he wanted his tombstone to read, “HERE LIES THE HEART AND SOUL OF A SCOUT.”8 The job was not just about keeping secrets, though that is how he earned the nickname “The Sleuth.” To Jerry Krause, the job was about solitude. You sit by yourself, take your own notes, keep your own counsel, draw your own conclusions.

His gift as a soloist made him a famed and successful talent evaluator. So let’s be real here: Jerry Krause BUILT the Bulls. Spare me the nonsense that “Krause didn’t draft Jordan. How hard could the rest be?”

Hard.

In 1987, Krause rescued Phil Jackson from the CBA. Jackson was ready to quit basketball. That one hire by Krause changed the course of the next 30 years of NBA history. Krause also pulled the trigger on firing head coach Doug Collins and promoting Phil.

Krause the Scout zeroed in on Pippen before his GM peers. Krause the GM wheeled-and-dealed his way to Pip landing in a Bulls uniform. Same can be said for Toni Kukoc. And his swap of Charles Oakley for Bill Cartwright — with Horace Grant ready to fill in for Oak — gave the Bulls their final pieces for their first run.

Incredibly, from 1993 to 1995, Krause took one three-peat team and retooled it on the fly to create another three-peat team. He spotted well-suited bargains in Steve Kerr and Bill Wennington, traded two career backups (Stacey King and Will Perdue) straight up for two starters (Luc Langley and Dennis Rodman), signed Brian Williams (later Bison Dele) for the end of the 1997 season to replace an injured Wennington, and acquired Scott Burrell for 1998, a guy who in one season somehow won MJ’s respect and a spot at his card table.

Krause’s post-dynasty rebuild did not go as planned — a story for another day9 — but there’s a reason this man’s got a banner hanging from the United Center rafters. I suspect he'll even rightly make the Naismith Hall of Fame. (Update: He did!)10

But like everything in Krause’s professional life, his strength in one area often became a weakness in another. And his desire to be one of the guys combined with a desire to unearth the next hidden gem combined with his desire for validation combined with his poor social skills had one clear outcome: his team found him maddening.

Scottie Pippen, 199511, describing why he wanted to be traded: “The relationship between Krause and me is hate. Trade me or Krause. They could send me anywhere. Nowhere would be as bad as here.” There’s more from Pippen on Krause in this interview with the late Craig Sager:

Phil Jackson, 1997, describing why Krause was the only key member of the team for whom he would not buy a book: “In the end, I didn't buy him anything because I couldn't find it in myself to give him something of value.”

Michael Jordan, 1998, describing what could bring him back for the 1999 season: “One thing is for sure, money won't keep me in the game. Never. Just change ownership. And you know what I'd consider a change in ownership? Change the GM. Let Phil be general manager and coach. Krause? I don't want to start a war around here. I'll just say that sometimes it's tough working for an organization that doesn't show the same type of loyalty toward you as you show it.”

When Krause arrived back in Chicago in 1985, he and Jordan got off to the wrong foot, literally. In Jordan’s second season, Krause tried to use MJ’s broken foot and extended recovery as an opportunity to improve the team’s draft position. In the subsequent 12 seasons of Chicago Bulls basketball, Krause made enemies with his word and his deed. On the eve of the 1998 season, he dropped his most famous, and most misquoted, statement: “Organizations win championships12.”

“What I said was, correctly, ‘Players and coaches alone don’t win championships. Organizations do.’ That’s true,” Krause said last month in an interview with Adrian Wojnarowski of Yahoo! Sports.

“You’ve never really backed away from that,” Wojnarowski responded. “You still believe it.”

“Sure,” Krause said. His point was that the Bulls were more than one great player, and he of course was right. The Bulls won championships four, five, and six not just because they had the best player but because they had the best second-best player and the best rebounder and the best sixth man and the best pure shooter and the best coach and, yes, the best general manager.13

Yet Krause took his praise of “the organization” even further. He wanted the public to know that the team had the best marketers. The best trainers. The best salary cap guru.

“Irwin Mandel was tremendous with his knowledge of the salary cap,” Krause said last month, and indeed Mandel’s masterful manipulations helped the Bulls acquire Rodman in 1995. But these were back room tacticians. Not coaches. And sure as hell not players.

“Michael said, ‘What in the heck is Jerry talking about? He ain’t sweating out there like I am,’” Krause told Woj. If that quote sounds familiar, Jordan said basically the same thing in his 2009 Hall of Fame speech: “(Krause) said, ‘Organizations win championships’. I said ‘I didn’t see organizations playing with the Flu in Utah’.”

So yes, Krause pissed everyone else. And yes, Reinsdorf empowered Krause14.

But as Smith notes, “who, after all, quits his job and profession because he doesn’t like the assistant boss?”

What might (not) have been

That brings us to the final point about Krause and his complicated legacy: we might not have won in 1999.

That’s what all of this animus toward Krause regarding “the breakup of the Bulls” presupposes. Fans say, “He broke up a championship team!”15

The 1998 Bulls were a championship team. The hypothetical 1999 Bulls… maybe not.

Consider this:

Forget about the hypothetical 1999 Bulls. The actual 1998 Bulls, it can be argued, had no business winning the title. Ignore contracts and personalities and just look at some hard facts.

Their best player was 35 years old in the playoffs, the oldest Best Player of any NBA champion since the NBA-ABA merger, (with the exception of maybe 37-year-old Kareem in 1985, who also had 25-year-old Magic).

Their second-best player was a 32-year-old who missed 38 games with an injury and played only 26 minutes in Game 6 of the Finals. Their third-best player was a 37-year-old who Jordan said he had to treat like his eight-year-old son, grabbing him by the head to coax him to attention.

By the 1999 playoffs, Jordan, Pippen, Rodman, Harper, Longley, Kukoc, and Kerr were all over 30 years old. Unlike Rajon Rondo with the ’08 Celtics or Kawhi Leonard with the ’14 Spurs, the 1998 Bulls had no youthful bridge player who would learn to carry the load and become the team’s newest all-star.

That player was supposed to be Kukoc, but he couldn’t even score 20 points per game in 1999 on 17 shots per night in an eight-man rotation with Harper, Brent Barry, Randy Brown, Dickey Simpkins, Mark Bryant, Andrew Lang, and Kornel David.

Now let’s talk centers. In six NBA Finals, the Bulls faced Vlade Divac, Kevin Duckworth, Mark West, Ervin Johnson, and Greg Ostertag twice. Yes, they beat Shaq, Patrick Ewing, and Alonzo Mourning in the playoffs, but they didn’t have to tangle with a top center in the Finals. They would have faced two in 1999, Tim Duncan and David Robinson.

I’m not saying they couldn’t win. I’m just saying it’s no sure thing.

Bulls fans like to pretend that we only lost titles because we, I guess, stopped trying. I’ve argued that the Bulls would not have won eight straight titles if MJ didn’t retire. But don’t take my word for it.

“People say if I hadn’t played baseball for a year and a half, we would be going for our eighth championship in a row,” Jordan told Telander in 1998. “But I don't think so. After our three-peat. the atmosphere on the team wasn't the same. On this team we love each other. No jealousies, no animosities, no nothing.”

Dynasties die. No team wins forever. The 1980s Lakers needed four Hall of Famers plus three other all-stars plus another 20-point scorer plus one of the game’s best defenders to win five championships in nine seasons. Shaq and Kobe were two of the league’s five best players and only won three titles together. Kobe won five total. Duncan won five. Magic won five. Bird won three. The Miami Heat pulled in arguably the greatest single-season free agent haul in NBA history and won only two championships.

The Bulls won six in eight years. Jerry Krause acquired the talent. Phil Jackson shaped it. Michael Jordan drove it. Scottie Pippen soothed it. Jerry Reinsdorf paid it. They did it together. They broke it together, aided — and guided — by time, age, health, ego, need, anger, boredom, and restlessness. There was no Yoko. Not even Yoko was really a Yoko. Rest in peace Jerry Krause. You earned it.

Jack M Silverstein is a sports historian with Windy City Gridiron and the author of “How The GOAT Was Built: 6 Life Lessons From the 1996 Chicago Bulls.” Read it here, and say hey at @readjack.

Deremy is co-host of my favorite sports podcast, “Bigger Than the Game with Deremy and Jose.” Check the archives. (Check ‘em.)

The Krause animosity started early. Even by 1990, before any championships, the Chicago Reader ran a Krause profile penned by the great Ben Joravsky (a big Bulls fan), titled “Nobody Cheers for Jerry Krause.”

I missed this at the time, but another great eulogy came from Bulls biographer Roland Lazenby.

Phil was on to something. As we learned in an interview on ESPN 104.5 in Baton Rouge during The Last Dance, Krause actually first approached Floyd in 1989 about coaching the Bulls, before Krause fired Doug Collins and promoted Phil.

My piece Oct. 6, 2021: “Michael Jordan's 1993 retirement: everything you want to know”

My NBC Sports Chicago piece on MJ’s comeback, from March 2020, which I reprinted on this site for the 30th anniversary. (Hi Dyce!)

My real-time oral history of the end of the Bulls dynasty, from June 2018 in Chicago Magazine.

This is from Rick’s iconic “The Sleuth” profile on Krause in Sports Illustrated, March 1993.

That “other day” came six months later when I wrote this thread on the intertwining history of Krause and his Class of 2017 classmate Tracy McGrady.

Since sometime last week, I’ve been making my way through Scottie’s memoir Unguarded, and plugging quotes into my old pieces when I can. Here’s a huge one from the end of the book: “I realize now that plenty of times when Michael and I were critical of Jerry Krause, we should probably have pointed the blame at Jerry Reinsdorf. Reinsdorf made the important business decisions, not Krause. Reinsdorf refused to renegotiate my contract year after year, not Krause. Reinsdorf owned the Chicago Bulls. Not Krause.”

From Second Coming by Sam Smith

In his memorable Hall of Fame speech, MJ made time for Krause and his “Organizations win championships” statement.

The best summation of Krause’s view of himself came from the Tribune’s Phil Rosenthal, who told David Halberstam that Krause deserved more credit than he got but wanted more credit than he deserved.

Here is how Sam Smith explained it to me in May 2020, in an interview I have not yet published: “If you’re the CEO of the most successful company in the world, why should you be fired? In effect, Jerry Krause was the CEO of the most successful basketball team in the world. Whether he was liked by his employees or not is irrelevant. He is producing the highest level of production for his equity owners, the board of directors, whatever. They keep that person. You don’t lose your job if your company is successful. That’s all it was. Jerry’s moves were producing success. Nobody else’s were. So why would you fire him? That’s all. Simple as that.”

Looking back, this is a point I don’t still agree with in full. It’s possible that some of the Bulls fans who were angry with the team’s breakup aren’t angry because The Jerrys cost us ring #7, but rather because they felt like the team should have been allowed to fight to what Tim Floyd later called a “natural death.” That’s what Jordan told Ahmad Rashad years later (I think in 2013): “It was a very sad situation, because we never lost in the Finals. I never knew what it felt like. If you’re going to be king of the hill…” Ahmad: “Be the king until you’re not the king.” Jordan: “…until somebody knocks you down. And then you can shake their hand and say, ‘You enjoy it. Now you can see how difficult it is.’ But that never happened. Now we have to live the rest of our lives that, wow, we could have won 7, or we could have won 8, or we could have won 9. The LeBron thing. But we were halfway there. We could have done all that. But for whatever reason it wasn’t meant to be.”

It seemed pretty clear to me at the end that the dynasty had run its course, they were all beat up and burnt out. I'm glad they broke up the team at the top, rather than seeing them sputter to an early exit from the '99 playoffs, their legacy is stronger the way it is. Thanks for elaborating on the history further!