“When ‘The Jordan Rules’ came out, the first day, I went to Jordan. I went up to his locker. He had his head down, and I said, ‘Michael, I just want to let you know, you have any problems with anything I wrote, I’m here, and I’ll be glad to talk to you about it.’ He kept his head down, never said a word. He was always a lot bigger than me and a lot more important. He could have really made things difficult for me. He could have attacked me. And he never did.”

— Sam Smith, Dec. 2011

At the start of the 1991 season, the Tribune’s lead Bulls reporter Sam Smith set out to write a book about a young basketball team on the make. At its core would be Michael Jordan, the most exciting athlete in sports.

There was only one problem. No one wanted it.

“I got nothing but rejection letters when (I) started,” Sam told me in December of 2011. “‘Who’s this Michael Jordan? Why is he so special? He’s never won anything.’ New York is so New York-centric. They would have liked a Patrick Ewing story or something.”

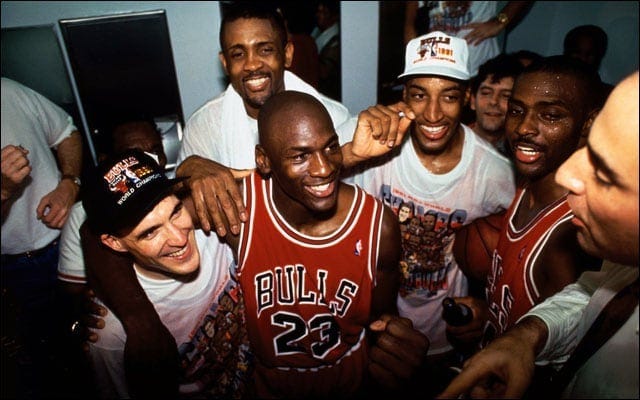

But his agent Shari Wenk wanted it. She sold it to Simon & Schuster. The Bulls won the championship. Suddenly, Sam had a sensation. His book was published in the middle of November 1991, was #7 on the non-fiction best-seller list by December 1 and almost immediately threatened to upend the team on its hunt for ring #2.

“I recognized this story going on that I couldn’t quite write in the paper, that Jordan was not a bad guy, but he wasn’t quite what he was depicted as,” Sam said.

You know all this already. What you might not know is the story of how Sam wrote it. On Dec. 24, 2011, 20 years after the book was published, he told me that story. I originally published that story on my blog on ChicagoNow. But when the Tribune shuttered ChicagoNow in August and straight up deleted the entire site, archives included, my interview with Sam was gone.

Fortunately, I keep backups. The portion of our interview that covered “The Jordan Rules” was actually part two of three. Part one, also no longer online, was about how Sam got his newspaper start as a general assignment reporter with a focus on politics, ultimately joining the Tribune in November 1979. The paper moved him to the business section around 1981. He didn’t care for that and asked to go to the sports section.

But they didn’t have an opening just then and sent him to the Sunday magazine instead, where he wrote a feature on a young CBA coach who Sam — a New Yorker — enjoyed watching play with the Knicks a decade earlier: Phil Jackson.

“Phil was on the verge of being out of basketball then,” he told me. “He was driving the bus. I was much more important than Phil then. You know, I was working for the Chicago Tribune, a national writer for one of the biggest papers in the country, and Phil’s driving a bus for the Albany Patroons. So it wasn’t like, ‘Oh my God, here’s this famous guy.’ It was, ‘Here’s another interesting guy.’”

By the time the paper had an opening for Sam in the sports section, Phil was building his coaching bonafides in the CBA. Jerry Reinsdorf bought the Bulls, Rod Thorn drafted Michael Jordan, Reinsdorf fired Thorn and replaced him with Jerry Krause, Krause steered Phil to the Bulls as an assistant and the seeds for the dynasty — and “The Jordan Rules” — were in place.

And that’s quite enough of an introduction. Sam told the rest of the story much better than I would be able to. For posterity, and because it’s a terrific conversation, I am sharing that interview here.

Best,

Jack

This interview, from December 2011, has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell me about getting started on the Bulls beat at the Tribune.

I went down to Sports and they had me do some general stuff. I was having a great time. They’d add you to things — when the Bulls were hot or the Hawks were hot or the Bears were hot, I’d write the fifth sidebar. It was great fun. I was at games and all that. And then when Jordan came I had a few assignments.

In fact, on his first day in Chicago I spent the day with him. I did a freelance thing for Us Magazine, which then was not quite like it is now. It was the first day he met the media. I went up and spent the day with him at his apartment. He was living in a three-bedroom townhouse up in Deerfield.

I liked Jordan a lot. He came out of a very stable family, a very stable basketball program, and when he came to the Bulls he really wanted to be a guy to just fit in and play. But he was so much better than the others. I remember Kevin Loughery — we were at practice, and they had no idea what they had, how good he was. He had been in the Olympics and Player of the Year, but they said, “Another good shooting guard.” Clyde Drexler was a good shooting guard the year before.

Then he started at that first practice. I remember the story: he called Rod Thorn, who wasn’t there that day. Rod was the GM, who’d made one bad draft after another, and Loughery said, “Rod, you finally didn’t screw up a draft.” Jordan just dominated the game. He dominated the practices.

But it was a different era. We traveled on commercial planes. We stayed at Holiday Inns and Sheratons. There was no entourage. He had three friends, and on their own dime they would come to some road games and hang out with him. He never slept. He had this incredible, like a humming bird thing about him. He could sleep an hour or two a day and be as fresh as you are. Constantly in motion. Just sort of a man’s man who was just fun to be around. Just joking and taunting and all that stuff. There was always action going on. Always joking and laughing and talking. I liked him a lot.

I kind of gravitated toward basketball, and then was put on the Bulls beat. I was a little reluctant. I didn’t want to travel around all that much with the team. But again, they insisted and said, “This is what you are doing,” and it just was the serendipity, the break of my life, because the Bulls got hot, Michael Jordan became the premier figure in sports of the era, and as an investigative reporter, my own background that I had, I was a little more aware and interested in stuff than I think other writers are or were. I recognized this story going on that I couldn’t quite write in the paper, that Jordan was not a bad guy, but he wasn’t quite what he was depicted as.

I’d been traveling with the team for a couple years, and I wouldn’t say I was getting bored, but I felt like I wanted more to do. My ambition was still not satisfied. And I would talk to different people, they would ask me about the team, and I would say, “Well, this is what happened, but this is really what happened.” People would be shocked.

Michael then was really sold well. He was in commercials. He was doing McDonalds, and Chevrolet, and Coca-Cola. There was the famous one where he delivered Cokes to a tree house — he jumped up into the tree house. He has a beautiful smile and is depicted as this perfect guy. I’d been around the team and knew he wasn’t quite that way. He could be very difficult. Players would complain to me about it. He would humiliate them at times.

I would tell people these stories, and people would say, “How come you don’t write – ” and I would explain, “The team’s winning, and you can’t write that in an 800-word newspaper story every day.” It just didn’t seem to fit. I remember one time I was having a conversation with Bob Greene, who later wrote some books about Jordan, very different than mine, but I remember him saying, “Do you realize what a figure you’re with?”

I often think about this because I read a lot of American history. Historical figures are not historic at the time they’re doing the things. Lincoln wasn’t a historic figure. He was just a figure who made everybody angry. When you’re going through it every day, when you’re there every day — I was at every game, and the whole year I’m with the team all the time — it’s just part of your life. It’s hard to step away and say, “I’m part of something special. I’m part of something historic.”

And they weren’t winning yet. We didn’t know if they were going to. The notion around the NBA was, “You can’t win with Jordan. He’s too selfish a scorer. He’ll be like George Gervin — a great scorer who’s never going to win.” Or a better player like Julius Erving, who was a big star and did all the dunking, but he didn’t win until he got Moses Malone.

I always like to try things to see if I can do them. Because I found out in Washington that, you know, I can do what they do. These guys are not so smart. I thought, Well, I can write a book. Doesn’t seem so hard. (Laughs.) I’ve got a story here. There was a publisher right across the street from the Tribune, a very small publisher, and I went up and called the guy and said, “I’ve got this story,” and told him some of the anecdotes. They were explosive kinds of things.

So he said, “I just hardly have any money.” I said, “It’s going to cost me extra time.” I had a 2-year-old at the time. I wasn’t making much money: $27,000, I think. I said, “I’ll need some money for babysitting and to buy an extra computer,” and he said, “I can offer you like four thousand dollars.” I asked him for like six or something. We were really close. I almost signed with him.

I went back to the office, and I was thinking about it, and a friend of mine in sports, Mike Conklin, said, “I’ve got a friend who’s an agent. Maybe she can give you some advice.” So I call her. She was an editor for Contemporary Books. I told her the story, and she said, “Don’t do anything, I’ll take care of that.”

The interesting part was that I got nothing but rejection letters when she started. She went to New York with it, and the publishing companies were either, “Who is this guy? We’ve never heard of him. Just a writer in a newspaper in Chicago. Who’s he to write a book?” And the other half were, “Who’s this Michael Jordan? Why is he so special? He’s never won anything.” New York is so New York-centric. They would have liked a Patrick Ewing story or something.

Finally Simon & Schuster gets interested and they offer a modest advance, like $20,000, but it was more than the four, so that was fine with me. Then she got another publisher interested and they raised that to like $40,000, something like that. So I signed a contract to do it.

I don’t have any regrets — I was doing the right thing and did the right thing for the newspaper — but the notion was, “Why wasn’t this stuff in the newspaper?” Well, in doing it, I would go to practice, I would do the media stuff, and then every day I would have a lunch or dinner or spend the afternoon with one of the players. I gathered so much information that the newspaper benefited. A guy was going to sign a contract, a trade was coming up, and I wasn’t going to save it for a book. So the newspaper was getting a tremendous amount of information.

But I got a lot of criticism afterwards that I was saving all of this good stuff for the book. I didn’t feel I was doing that because I was working like on a two to three months lag. When it was January for the Bulls, I was gathering November stuff. I would do my job, and then as I went with the players I would go over the last month or two, things that happened, get my anecdotes, talk about games, say, “What about this?” And sort of filled it in that way. I did the beat and the book simultaneously.

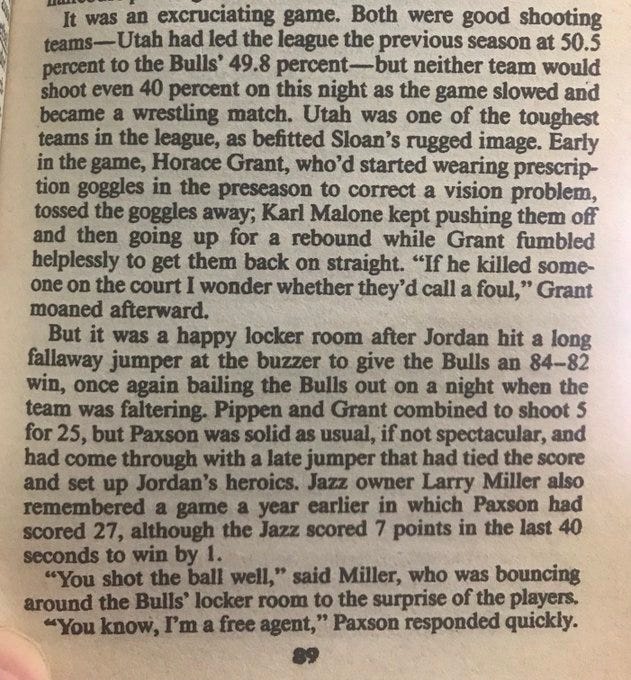

Example of the differences between Sam Smith’s daily reporting vs. how the game appeared in “The Jordan Rules”:

Nov. 13, 1990, Bulls 84, Jazz 82

I modeled it after Halberstam’s “Breaks of the Game.” He wrote this book about the Trail Blazers. It was my favorite sports book, and I thought at one time that if I ever wrote a book, this was the kind of book that I would want to write. It was a guy getting all of the behind the scenes stuff. That’s exactly how I modeled it. I copied what Halberstam had done with the Trail Blazers in ’78. He missed the championship year. His book was better written than mine, but mine had Michael Jordan. He had Bill Walton in a cast.

I was writing my book as a diary of the team. I wasn’t writing “The Jordan Rules.” I was writing this story of a team going through a season. Because I remember thinking during the season, you know, Jordan could break his leg. I didn’t think they were going to win the championship. Nobody did. Phil didn’t. None of them did. They still doubted if they could beat Detroit. They just didn’t know if they could do that.

That whole season was just all about, “Can we beat Detroit?” Early in that season they got blown out by Detroit right before Christmas. And it was like, “What did we accomplish? We might have to break up this team.”

So I was doing Halberstam’s book to just try and write a diary of a season. But I finish it and they win! And it becomes a national story. I didn’t want to focus it on Jordan. I wanted to focus it on the team. But my agent came up with the title, because I’d written a little section about the Jordan Rules in it, the difference between what the Pistons played and what the Bulls players called the “Jordan Rules.” She was the one who suggested that title, and obviously that had a lot to do with it being a commercial success.

But it is so much more than just Jordan. All the stuff about Pippen’s contract, and how Phil motivated Pippen vs. how he motivated Grant, and Pax and free agency, and Hodges and his farm…

That was the book I was writing. The team dynamic. How everything impacted off one another. What it was like to be inside the team. Because that’s what nobody ever knows in sports. We hear what they say and we watch the games, but nobody knows what really happens.

It’s sort of like the essence of the third paragraph of any good story. The first two paragraphs should tell you what happened, and the third paragraph should tell you what it means. And very few writers do that or do it well. I wanted to write a book saying, “This is what it means. This is what really happens. This is what it’s like.” That was my whole point.

I told every player on the team before the season started, “I’m writing a book about this team, about this season. You may not like everything in it, but nobody’s going to lose their job, and nobody’s going to be embarrassed with their family.” And that’s what I did. I’m not a fan of hit-and-run journalism where you can endanger someone’s life — well, not endanger, but hurt their career or cost them their job, and then you never show up again. I was going to be there all the time, and I was coming back. I told them that.

I wasn’t going to write about cheating on their wives on the road, running around. I didn’t write about Jordan’s gambling with characters. I knew a lot of that stuff that would be embarrassing, and that today would be written about. I thought it was just cheap, salacious stuff, and I wouldn’t feel proud of having done it and I’m glad I never did do it.

But the stuff that you WERE writing about that came as such a shock to a lot of people, why did you feel like that was a story that HAD to be told?

Because that all happened at work. That was my view. This is what goes on in the gym. This was a basketball story. Not just about pick-and-rolls and stuff like that, but being part of a basketball team. I wasn’t writing about what you were doing on the weekend. I was going to humanize it to an extent. Tell you what these people were about. I held to that.

When the book came out everyone was pulling quotes out of context. I was under siege. I was trying to avoid a lot of it because I was shocked on some level. I’d become so inert to the story that I just didn’t think it would be that big a deal. I’d been living it for three or four years. So it was shocking to me. I was getting heavily criticized and threatened and people were blasting me on radio shows and TV shows. Mike Ditka called me names. The book had hardly been out. None of those guys had read it. Just, “Michael would never do this.”

People were really angry. I was getting threats. It was very difficult. But I’d been taught a couple of good — my mentor in journalism was my first editor in Fort Wayne who hired me to be the investigative reporter, Ernie Williams, and I did these tough investigations. I cost people their jobs. I got a mayor knocked out of office. A lot of people suffered from things I was doing. (Laughs.)

One of the things he told me — and he made me do it all the time — he said, “These are tough stories, but they have to be accurate. You have to stand behind whatever you write.” So the day the story would come out, I would go see the subject I wrote about. They might not want to see me, but I went to see them. I was letting them know that I was standing behind this story. Every investigative story I did, he made me do that.

So when “The Jordan Rules” came out, the first day, I went to Jordan. I went up to his locker. He had his head down, and I said, “Michael, I just want to let you know, you have any problems with anything I wrote, I’m here, and I’ll be glad to talk to you about it.” He kept his head down, never said a word. He was always a lot bigger than me and a lot more important. He could have really made things difficult for me. He could have attacked me. And he never did.1

I had a good relationship with him. I played golf with him. I’d been out to dinner with him. But that was over with. No more. I used to joke around with him a lot in the locker room. Pick on him. He liked that. “I see you missed your first ten shots today. Nice going.” I’d still ask him questions in media sessions, and he’d answer them professionally, so he maintained a very professional view of it.

I know a lot of his friends were telling him, “Blast this guy. Go after this guy.” He would never do that, for whatever reason. And I was always personally grateful he didn’t. I didn’t have to apologize for the book because I knew it was accurate, but he could have made life a lot more difficult for me at the time. (Laughs.)

SILVERSTEIN: I went down to the library today, and I was looking at your stories from that time and comparing them to the book. There was a win against Washington February 19th, and there was a huge difference between the quote you got from Jordan for the paper and the quote from him in the book. I know you told the players you were writing about them.

But were there moments where somebody says something to you or in front of you, and you realize, “Oh wow, that’s a great bit, I know that I’m not going to write about it in the newspaper, and this guy doesn’t realize that just because he’s not going to read it tomorrow, he’s going to be reading about it in six months.”?

No, I never thought of it that way as much. There were two elements. One, a lot of those kind of things I would get later on. I might get something about that Washington game two weeks later, but there was already other stuff going on. And there were a number of things that I wrote about in the book that I wrote about in the paper, like how he punched Will Perdue. That was written about in the paper, but in the book I would get to elaborate on it and go into greater detail, which you wouldn’t do in the newspaper.

There were also times when players would say to me, “This is not for the daily newspaper.” Because they knew I was writing a book. The guys would say, “You can use this later, but not now,” because once you put something controversial out, guys have to answer to it. I did something like that in the playoffs with Grant, where he was mad at Jordan. I wrote that story for the paper where he called out Jordan or something, and then they really all got on him, all the players and the coach, and said, “You’ve put yourself on the line, and you have to go out and have a big game,” which he actually did. He had 17 rebounds against the Pistons or something.

It was a balancing act on some level because I made some agreements with players. It was an off-the-record sort of thing, or background, where somebody would tell you something but you can’t use it, but you can use it for perspective. So a lot of that kind of stuff I used for perspective in the newspaper to tell the overall story. Guys would say “I don’t want to see that in the paper tomorrow,” and then they would talk about it.

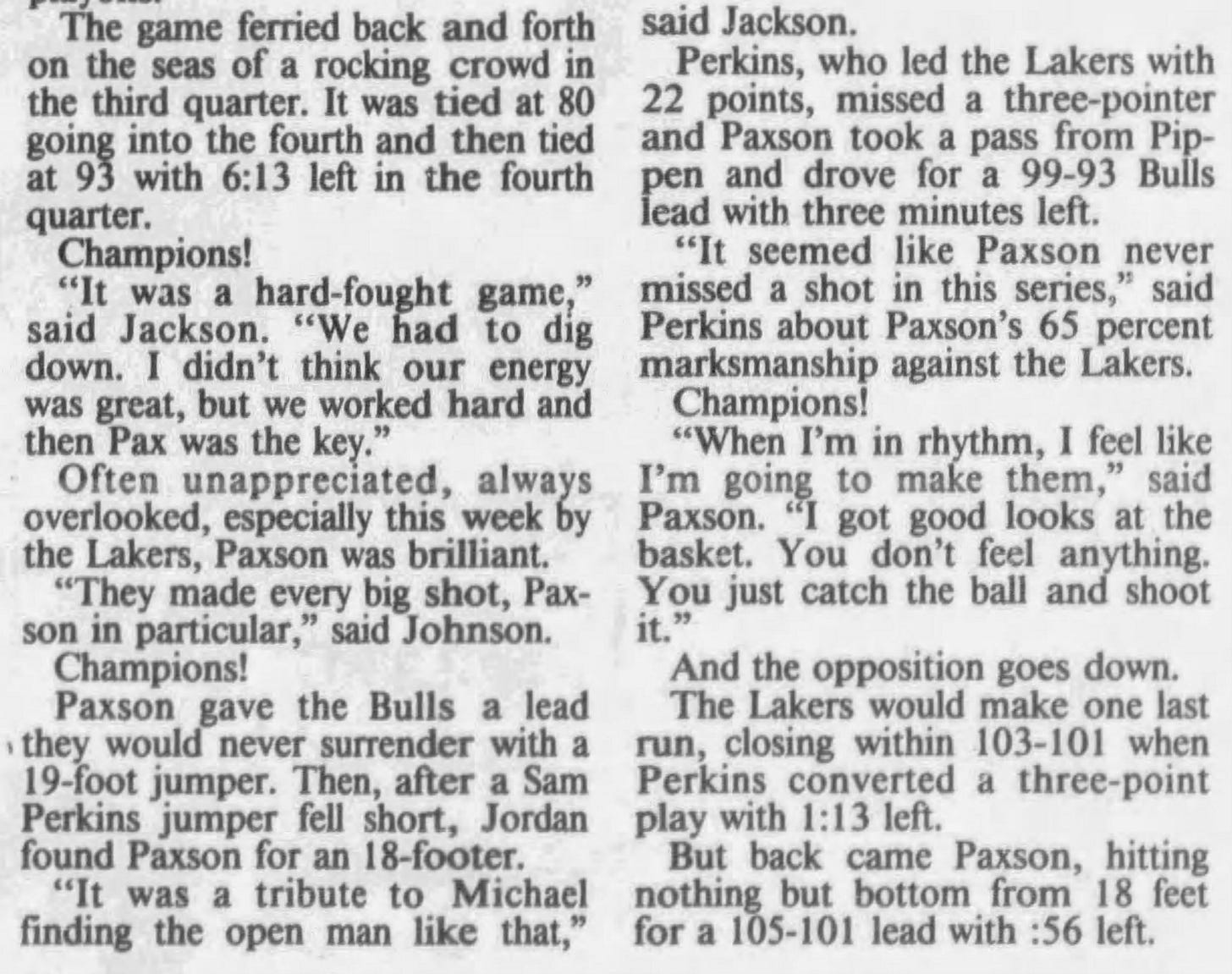

Like Phil. After the last game, there was a great thing, a wrap up to the book actually: that time-out with six minutes left against the Lakers. “Michael, who’s open?” Phil volunteered that story to me. He understood what I was doing all along. I mean, I wasn’t asking him about it. It was chaos in that game. I didn’t notice that there was something different going on in that timeout. He’s always talking to Michael in timeouts. He stopped me after we got home after the championship and said, “Why don’t you save that for your book. Don’t put that in the newspaper.”

From pages 347-348 of “The Jordan Rules”:

Jackson huddled with the coaches near the free-throw line while the starters took seats, as was the custom in time-outs. Jordan usually liked to peer out into the crowd during time-outs, but for the most part in these playoffs, Jordan had been attentive. Jackson liked the eye contact he was getting from Jordan, and on several occasions just nodded to him in an unspoken “Okay, take over.” But Jackson didn’t like what he was seeing now. He decided to be sharp with Jordan.

He kneeled in the huddle and stared into Jordan’s blazing eyes.

“M.J.,” he demanded, “who’s open?”

Jordan looked at him and didn’t answer.

“Who’s open?” Jackson asked again.

“Paxson,” Jordan said.

“Okay, let’s find him,” Jackson said.

He clapped his hands and the team went back onto the floor.

In those first two years, in ’92 and ’93, what was the team’s and the players’s reactions to working with you? Did anybody shun you? Did anybody thank you?

It was a little uncomfortable with Jordan, because he really wasn’t talking to me anymore. But I had a great relationship with the other players, because a large part of doing the book was players saying to me over the years, “You got to write something about this guy. You’ve got to tell this story. Nobody wants to tell this story.” I would always say to them, “I’ll put it in the paper. I’ll quote you. Whatever you say.” No, no one ever wanted to do that. But they wanted me to do it.

All these stories I got about things he did, they came from the players. I wasn’t at these practices. I’m not inside. It was like Woodward and Bernstein. How’d they know what Nixon and Kissinger were talking about? They weren’t there. Someone tells you the story. That’s who told me the story — players. They were growing uncomfortable with Jordan’s dominating personality, and they didn’t mind seeing him knocked down a notch, if you could say.

So the relationships with the players all got better. They would come to me and confide in me this or confide in me that. I never had trouble with anybody. In fact, when it was really getting bad, when I was really under siege the couple of weeks after the book came out, a couple of players called me at home. Bill Cartwright was one. Horace Grant. B.J. called me and said, “You’re fine, don’t worry about it, this will blow over.”

Because I was pretty shaken. I’d be outside — people didn’t know who I was, it wasn’t a big media era where you’d be on TV — but I’d be in a public place and I’d have people condemning me. Several of the players called me and reassured me. I didn’t call them and ask for reassurance. They knew I was getting beaten up so badly in the media, and they said “Don’t worry, you’ll be fine. You’re always welcome.”

My colleagues were really mad too. It was a combination I’m sure of jealousies, or trying to suck up to Michael. They figured if they ripped me Michael might appreciate it more, because everybody was trying to get close to Michael all the time. The Sun-Times was going berserk. They were making up stuff. Boston Globe did some of that. Boston Globe wrote a whole story that “The Jordan Rules” was devoted to telling the sexual lives of the players. And there was not a single word about the sexual lives of the players in “The Jordan Rules,” but the Boston Globe wrote a whole story saying that’s what the book was about.

I was grateful to a number of these players, and over the years I’ve maintained good relationships. I still talk to a number of those guys. Brad Sellers I’ll talk to occasionally. Dennis Hopson. B.J., who’s around. Cartwright I see and I’m very friendly with him. At the time, they were very supportive. So I felt comfortable going to games because the players were welcoming.

What about King? Because he sort of gets it bad, and I could see him as a young guy –

Well Stacey — yeah, I was hard on Stacey. The little uncomfortable part is now, because I work with Stacey. The last couple of weeks, Comcast was running old Bulls games and we were doing the commentary. And I traveled with him occasionally. So I felt guilty a little bit.

But at the time, I was telling the story of how they felt toward Stacey. It was just part of it. I had nothing against Stacey any more than anybody else, but that was what was going on with Stacey. They were beating him up badly, and I was witness to it.

I remember Jordan shut out Sports Illustrated after the whole baseball, “Bag it, Michael!” thing. Was there anything like that?

Never. He never did that. He always dealt with me professionally. When he came back in ’95-’96, I did have some private conversations with him. But not about the book. He’s never raised any question about anything I’ve ever written. Never asked me about anything about the books. I had some private conversations with him, but about basketball. I’d get him alone at practice or at a road game and ask him a few questions about this or that, and he was fine.

I did see though, there were times right after the book came out — there was always a routine after the game, there’d be people waiting for him to sign autographs, so the season the book came out, people would hand him my book to sign, because his picture was on the cover. And I remember him saying a couple of times, “I sign anything but that.” That’s the only thing I’ve ever heard him say regarding that.

A lot of writers who eventually read the book finally, said, “This is not so bad. It humanizes him. It says some days he a dick, but so what? A lot of people are a dick some days. But he’s not a bad guy. He’s not a criminal. And he basically has a good heart.” And so later on now, when he went to the Hall of Fame — because the speech he gave at the Hall of Fame was like “The Jordan Rules.” He told all my — in fact, when I was sitting there with one of the members of the Bulls staff, when he was going down this list of people who had motivated him, the guy poked me in the ribs and said, “You’re next.” He thought he’d be mentioning me. I thought so too, as he was going down this.

That became who Jordan was: this guy who was a great competitor, sick almost, who would do anything to anybody to win. And that became a positive. People celebrated that. Michael had to do these things to get where he wanted to go. People who read “The Jordan Rules” now say to me, “What was so bad about that book? Why were people angry about that?” Because now they know Jordan, that’s Jordan, and they accept that, and they still like him. This just shows him to be human. We were trying to make him non-human. Superman. And there is no Superman.

He’s a great success. People want to identify themselves with success. People who are special. And he’s viewed as special in what he’s done. The things that have come out — and all of those things came out after “The Jordan Rules.” The gambling with Slim Bouler, and the woman stuff, and I’m proud to have never mentioned any of those things. The point too is that much more serious allegations or circumstances have developed since any of my books, and I think “The Jordan Rules,” and I’m not taking credit, but I think it relieved him too. He was trying to be perfect all the time because he was being sold as that. And I think my book gave him the excuse that he doesn’t have to be perfect but he’s still going to be liked.

Because I remember one time, I asked him, “What’s the thing that scares you the most?” I thought he was going to say about somebody dying or something, and he said losing his endorsements if people came to see him as something he wasn’t. (Laughs.) And I was so interested in the response, because that was the last thing I was expecting.

That was in the 80s some time. ’88 maybe. I think his handlers were all telling him how perfect he had to be, and I think he was struggling to have to live up to that. In a way, even though he was not happy with my book, I think it freed him some to be who he could be and still be beloved. People have accepted that hey, he’s not perfect, but you know what? He’s not a child molester. He’s not a murderer. He’s done some stupid things, he’s said some stupid things, but we still kind of like him. He’s a fun guy, he’s a decent guy, and he’s a great performer. And what’s wrong with that?

All newspaper clippings from Newspapers.com.

Jordan’s reaction, from his 1993 book “Rare Air”:

“I knew that, at some point in time, people were going to start taking shots at me. When you’re on top, some people want to knock you down. I can accept that. But I never thought that it would be someone that I knew, someone that I had spent time with and someone that I had been frank with on a lot of subjects. That’s what bothered me most about the book The Jordan Rules. There was never any confrontation, nothing to make me aware of what was going on. That was just selfishness on the part of the writer. If that person was the friend he pretended he was, then why not at least let me know what you’re doing behind the scenes. Instead he kept it under wraps and then bam, it hits the papers. I felt betrayed.”