“A lot of writers who eventually read the book finally, said, ‘This is not so bad. It humanizes him. It says some days he a dick, but so what? A lot of people are a dick some days. But he’s not a bad guy. He’s not a criminal. And he basically has a good heart.’”

— Sam Smith, 2011, on the impact that The Jordan Rules had on Michael Jordan’s image

Michael Jordan is a good person.

Michael Jordan is a flawed person.

I suspect those traits explain MJ’s unusual 1992-93 preseason.

For Jordan’s first eight Bulls seasons, he never missed a preseason game. In his ninth, he missed three. It’s a pattern change that jumps off the page: what could make the world’s most competitive athlete and purely enthusiastic hooper miss three games in nine days? Was it injury and illness, or an overlapping legal matter?

And though he missed three games, he added one, literally: a charity preseason game for Hurricane Andrew victims, driven by Jordan after the schedule was originally announced.

Let’s take a look at his rather eventful month of October 1992.

Michael Jordan's preseason obsession

“You can do all the running you want, but practice is practice. … A game situation is different.”

Michael Jordan and Hurricane Andrew

When Harvey Gantt was running against U.S. Senator Jesse Helms in 1990, Sam Smith asked Jordan why he wasn’t publicly supporting Gantt against the racist Helms. Jordan’s mother had also asked her son. Jordan jokingly told Sam that he was sitting out the race because “Republicans buy shoes, too.”1

Sam published the quote in his 1995 book Second Coming2 and it immediately branded Jordan as an apolitical capitalist opportunist. After Jordan retired in 1999, I was not surprised to see a writer use the quote as the centerpiece for an article lambasting Jordan in comparison to Muhammad Ali.

Sam later published in 2014 that Jordan was joking with his “shoes” quote, acknowledging that publishing the quote had gotten Jordan into trouble.3 Jordan clarified his position in The Last Dance:

“I wasn’t a politician when I was playing my sport — I was focused on my craft,” he said. “Was that selfish? Probably. But that was my energy. That’s where my energy was.”

What I think about Jordan is that he viewed his basketball play as having two key philanthropic functions. One, he viewed his basketball abilities as his societal contribution, same as any artist who creates a piece of work and bestows it upon an audience. Two, on a personal level, he was able to give his time to people in need; he became renown as one of the biggest ambassadors of the Make-a-Wish Foundation, giving both time and money and eventually the largest single donation in the foundation’s history.

I think both of those came together in the wake of Hurricane Andrew crushing South Florida.

The hurricane made landfall in August of 1992 as a category 4 and quickly moved to category 5, one of just five category 5 hurricanes to hit the U.S. mainland. Andrew devastated the Miami area, with $27 billion in damage ($60.5 billion in 2024 dollars), destroying over 125,000 homes and leaving at least 160,000 people temporarily homeless in Florida’s Dade County, broadly known for Miami.

The director of FEMA said Andrew caused “more destruction and affected more people than any disaster America has ever had.” One hurricane expert explained its power as “a Mike Tyson storm.”

On Sep. 16, before training camp and about a month before the preseason, the Bulls added a charity preseason game with the Heat for Oct. 19 in Miami. All proceeds went to Andrew foundation We Will Rebuild, Inc.; the game was broadcast on both TNT, which aired an 800-number for donations, and SportsChannel, which broadcast the game without commercials, treating it as a telethon.

Jerry Reinsdorf and Heat managing partner Lewis Schaffel each credited Jordan with launching the game, which MJ developed with Heat minority partner Billy Cunningham on a North Carolina golf course two days after Andrew hit.

“Michael said, ‘What can I do? I want to do something,’” Schaffel said at the September announcement. “So the idea came about for a special game that would give us the opportunity to raise a great deal of money. Michael has called a couple of times since to see how things were going. One time he said, ‘I’m not going to play hard in the other preseason games, but this one count.’”

The Slim Bouler problem

Entering the 1992-93 preseason, MJ was carrying major miles.

His 80 games in the 1992 season were the fewest of his career other than his injured 1986. Since 1990-91 he had played in every preseason game, every playoff game, every All-Star Game and 15 Dream Team games. In a training camp interview, Sam Smith and Phil Jackson talked about the possibility of Jordan missing some of camp or some preseason games.4

So at first glance, nothing looked too weird about Jordan missing the first ‘92-’93 preseason game with an injury. John Paxson and Bill Cartwright were out too.

But one of the starters in that first game was Scottie Pippen, who was logging just as many miles as MJ. Since the 1989-90 season, Pippen had played 82 games and double-digit playoff games every year, and then the same 15 Dream Team games as Jordan, along with the All-Star Game in 1990 and 1992. By the ‘92 preseason, Pippen had not missed a Bulls game since the final preseason game of 1990.

One major difference between Jordan and Pippen in October 1992: Pippen was not under federal subpoena.

When the Bulls opened the ‘92-’93 preseason against the SuperSonics on Friday, Oct. 16, Jordan was listed as out due to a bruised wrist from practice the day before, his first practice of the season. He may well have hurt his wrist. He was also headed for court the next week to testify in James “Slim” Bouler’s drugs and money-laundering trial.

Jordan’s troubles started in November of 1991, when the feds seized from Bouler a $57,000 check that came from Jordan.5 Jordan and Bouler claimed the money was a loan to Bouler to build a driving range. Then in February of 1992, a bail bondsman named Eddie Dow was murdered in a robbery at his home in North Carolina. Found in his briefcase were three checks from Jordan totalling $108,000.

David Stern had heard enough. The commissioner called Jordan to his New York office in March for a meeting about his gambling activities and his associates. The NBA publicly absolved Jordan of wrongdoing and advised him to be more careful.

Fast forward to October 8. Jordan was subpoenaed and would have to admit that he had not loaned Bouler money for a driving range but had lost that money to him gambling.

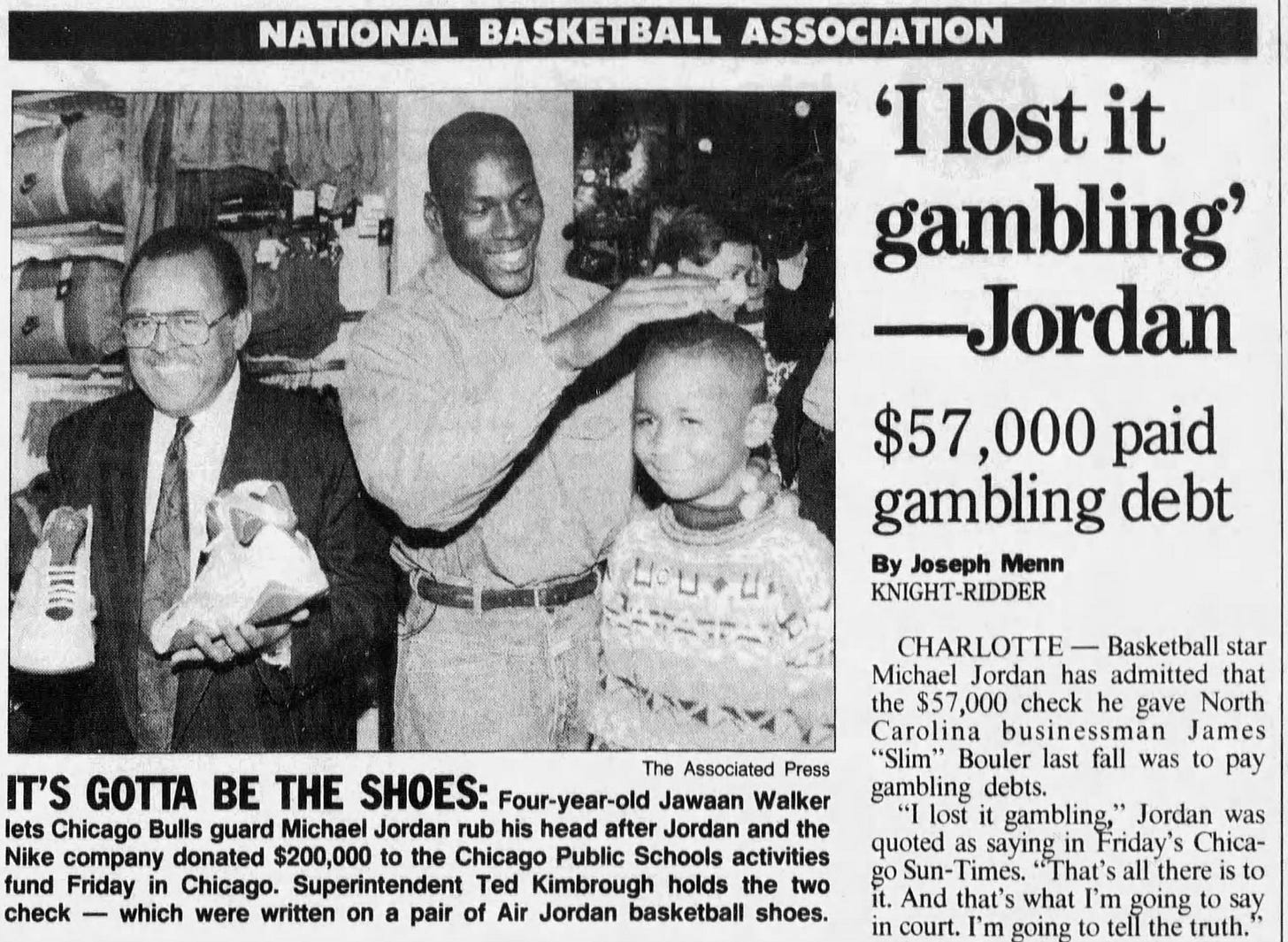

The Bulls opened the preseason Oct. 16 at home. Jordan spent the early part of that day at a Chicago Public Schools event, where he and Nike donated $100,000 apiece to CPS to help cover a budget shortfall that had threatened district-wide sports programming. The schools superintendent celebrated the donations, noting that they saved the programs “for this year.”

Jordan’s goodwill was a fantastic photo op, as MJ and Nike attached each check to an Air Jordan sneaker, which Jordan then signed. (Even with the photo, I’m not totally sure how this worked.) Yet breaking news from the Sun-Times that day was a story in which for the first time, Jordan admitted that the $57,000 he’d given Slim Bouler was not a loan, as he previously stated, but was for gambling losses.

The CPS donation event turned into an MJ gambling press conference.

“I will show up (to court). I won’t run, and I’ll answer the questions that are put to me,” Jordan said about testifying.

Game off, game on: giving back to Miami

The Heat fans were ready. So were the Bulls and Heat. So was Michael Jordan.

MJ joined his teammates in the preseason schedule on Saturday, Oct. 17, with a game in St. Petersburg, Florida, against the Washington Bullets. He scored 19 in 16 minutes in the Bulls win, and then had a day off before the sold-out Hurricane Andrew game at Miami Arena.

“(Jordan) arrives in Miami as a public paradox,” wrote Miami Herald sports columnist Shaun Powell in an Oct. 19 column with the headline “Saint or fiend: What image awaits Jordan?” Powell acknowledged the challenge of understanding Jordan in a week when he would both play in a charity game he himself helped organize and testify in a drug and money-laundering trial.

“Jordan was never as angelic as we made him to be … nor, I suspect, is he the back-stabbing opportunist that’s being portrayed now,” Powell wrote. “He’s probably a lot like you and me, a person whose emotions and instincts make him do the right and wrong things.”

The Bulls and Heat held a basketball clinic at Miami Arena for 12,000 hurricane-impacted schoolchildren, and then played their exhibition game that night. The game drew a sellout crowd of 15,008, and the Heat gave floor seats to more than 700 children. Jordan and Horace Grant led the Bulls with 15 points apiece. The Bulls won 111-94.6 Ticket sales grossed $400,000.

“Being millionaires, we felt a sense of obligation to come and help people who mean so much to us,” Jordan told the crowd over the p.a. system. “We consider Miami part of our family — our NBA family. Hopefully the money raised will give you a little more determination to rebuild.”

Interestingly, the Bulls had brought a reprieve to the Miami area four seasons earlier, when a Bulls-Heat game in Miami slowed severe rioting after a police officer shot and killed a Black motorist.

“We went to Miami and they were rioting in Overtown, and it came time for us to come down and they stopped rioting,” Craig Hodges recalled. “From that point in time, I understood the impact of Michael Jordan and the Chicago Bulls.”

The meaning of “goodness”

The day after the charity game, the Bulls were in Syracuse for their preseason game against the Nets. The trial date had moved a few times. Jordan was initially supposed to testify on Oct. 19, the day of the charity game, but the trial ended up starting the next day, with Jordan scheduled to testify on Thursday.

The Bulls were off for two days, and on Thursday Oct. 22, Jordan arrived at the federal courthouse in Charlotte. Attempting to stay under the radar, he sent a decoy limousine to one entrance and emerged nearby from a Nissan Pathfinder. The ruse mostly failed: a handful of photographers and reporters still caught up with him as he entered court. That was his final bit of evasiveness for the day.

His testimony lasted eight minutes, during which time he explained his connection to Bouler and the truth about the $57,000.

“It’s actually what I lost playing golf and gambling, and later in a poker game where he loaned me money,” Jordan testified7. Regarding his initial lie that the $57,000 was a loan to Bouler: “It was my immediate reaction to the media after a game,” he said. “It was strictly to save embarrassment and pain and the connections to the gambling.”8

Jordan finally got his rest over the weekend, when he missed back-to-back games, listed as having the flu. Preseason games are often held in non-NBA cities to give fans a chance to see their heroes up close. The first of the two games Jordan missed was in Albuquerque against the Timberwolves.

“The flu?” objected one 18-year-old fan in New Mexico. “My mom had a baby and she’s here.”

Another fan arrived with a sign reading, “I wanna be like Mike — if he was here.”9

Despite the disappointment, no ticket-holders asked for their money back. Jordan missed one more game, against the Nuggets, and was back with the Bulls on Monday the 26th, only his seventh day with the team out of 18. He chalked up the $57,000 loss to Bouler as “just bad golf in a three-day period,” and said he was “pretty sure” that he lost some fans. The emotional discomfort that contributed to his 1993 retirement was already on display.

“If for something that minor you want to jump off ship and say ‘I’m not a fan of Michael Jordan anymore,’ then they were never a fan of Michael Jordan from the beginning,” he said. “I’m past the stage of worrying about my image to the point where I’m affected by people not liking me because I’m a competitor in some instances. That’s something I’m able to deal with.”

He played the final three preseason games, but did miss four regular season games, playing fewer than 80 games for the first time in his career other than 1986. His worst gambling problems were actually ahead, not behind, as the Richard Esquinas affair, already playing out in the fall of ‘92, would end up contributing to Jordan’s 1993 retirement.

Much further ahead was Jordan’s public shift away from his “Republicans buy shoes, too” persona. In 2014, Scoop Jackson wrote about Jordan’s advancement of Black executives through Jordan Brand and his ownership of the Hornets.

“Outside of Nike president Trevor Edwards, the execs at the Jordan Brand have always been the highest-ranking blacks in (Nike),” Scoop wrote. “This is something that Jordan's made sure of; something that is not happenstance or a mistake.”

In June 2020, at the height of George Floyd, Jordan and Jordan Brand launched the Black Community Commitment (BCC), a pledge of $100 million over 10 years to organizations “dedicated to ensuring racial equality, social justice and greater access to education.”

“Black lives matter,” Jordan and Jordan Brand said. “This isn’t a controversial statement.” While many organizations and institutions have backpedaled on Floyd-era initiatives, to say the least, Jordan Brand has continued the BCC, steadily filling out the $100 million. Jordan has also been opening health clinics in his home state of North Carolina, four since 2019, focusing on filling health vacuums for uninsured patients.

Jordan’s actions today support his statements during his playing career. As a player he kept his focus on basketball in public, with charity in private. Now far removed from his playing days, Jordan has embraced his voice. That’s commendable and beautiful and the impact is real.

Yet the older I get, the more I am drawn to Jordan’s mission as a player: a man of superior gifts who flourished through simplicity, through the act of coming to work each day and saying, “I will do my best.”

Michael Jordan is a good person. Michael Jordan is a flawed person. His flaws have faded and his goodness has grown.

It took me a long time to see another truth, and I’m glad I can: his greatness was goodness, too.

-

-

-

Thanks for reading, everyone. And on a tragic note, RIP to Bobby Jenks. My salute to #45. Condolences to his family, friends and Sox fans.

The infamous quote has also appeared as “Republicans buy sneakers, too,” but Sam’s original quote in Second Coming was “shoes.” In 2016, Slate had a great breakdown of the quote, its sourcing and its impact.

From the preface, page xix

There Is No Next, page 12

MJ’s busy offseason: a championship on June 14 in Chicago, the Olympics qualifying tournament in Portland running June 28 to July 5, the Olympics running July 21 to Aug. 8 — and a fun barbecue and touch football game in Roseland in late August!

The check was dated Oct. 17, 1991, and covered losses that Jordan incurred in the first week of October, when his teammates were visiting President Bush at the White House. This was the visit in which Craig Hodges delivered a hand-written letter to President Bush about the plight of Black people in America, and also put on a shooting display with B.J. Armstrong. Jordan said that he skipped the White House to spend time with his family.

Incredibly, the Heat entered the exhibition 0-20 all-time against the Bulls, including preseason games and their sweep loss in the 1992 playoffs. They lost two more games to the Bulls in ‘92-’93 and finally notched their first win against us on March 11, 1993, a 97-95 victory.

Charlotte Observer, Joseph Menn, Oct. 23, 1992

Bouler was convicted on the money-laundering charges but acquitted on the drug conspiracy, ultimately spending eight years and 15 days in federal prison. After the trial, he said he felt good when Jordan said that Bouler had not played poker, just golf.

Chicago Tribune, Melissa Isaacson, Oct. 24, 1992