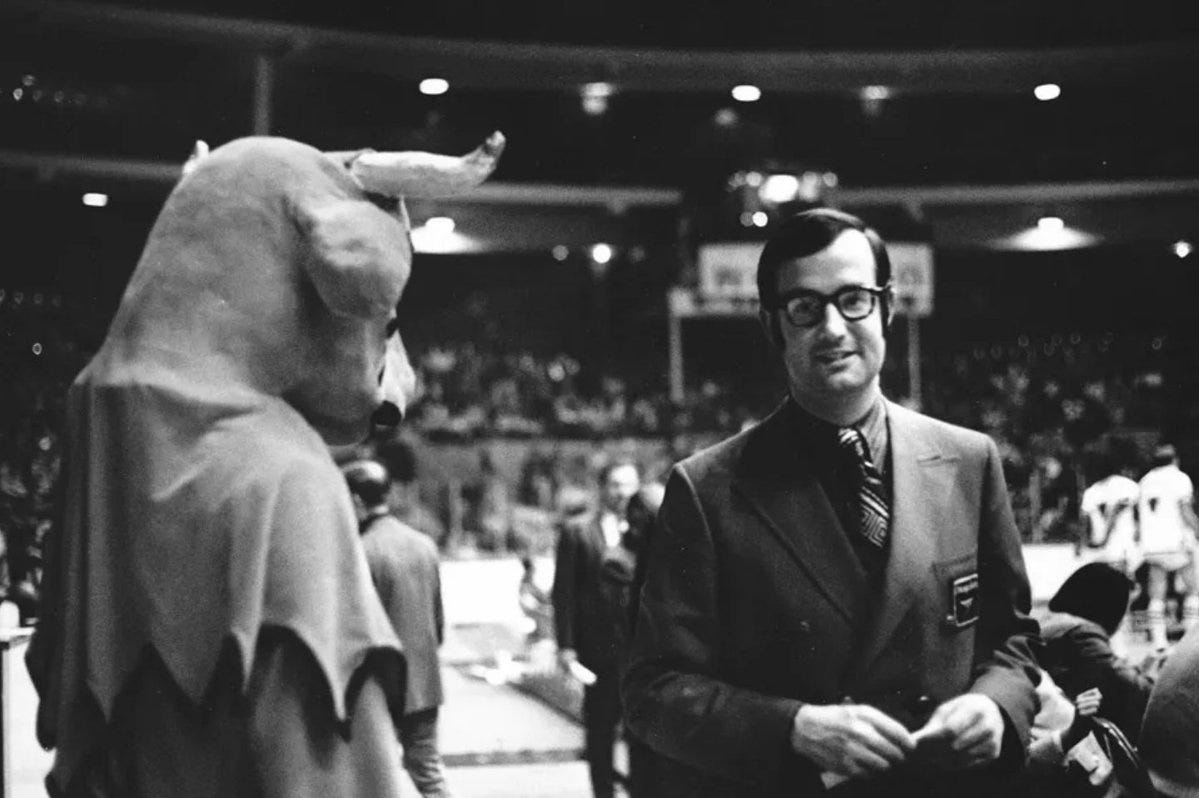

Pat Williams came to the Bulls in August 1969 knowing full well the fans would need more than a chance to wrestle the bear. They would need that too, naturally. All fans do. But rolling around on the Chicago Stadium floor with Victor wouldn’t be enough to bring fans to Bulls games. Hell, watching him, Pat Williams, the new GM, wrestle with Victor the Wrestling Bear, that wouldn’t do it either.

Chicago sports fans were drowning in ‘69. For the first time since 1958 the Black Hawks missed the playoffs1. The White Sox lost 94 games. The Cubs became “the ‘69 Cubs.” The Bears posted their worst record ever at 1-13.

They were all a bigger draw than the Bulls.

“You may have a hard time imagining the Bulls of ‘69 — a rock-bottom team with hardly any fan following, making no money, winning few games,” Williams wrote in 19972. Williams died Wednesday at age 84 from complications of pneumonia; he is remembered first and foremost as the founder and leader of the Orlando Magic, the man who brought the NBA to Disney World and famously won the draft lottery in back-to-back years3, selecting Shaq #1 in 1992 and trading back for Penny Hardaway in 1993.

That’s how I learned the name Pat Williams: he was the happy-go-lucky leader of the NBA’s newest hip franchise. Before that, he was the GM of the 76ers who brought Moses Malone and a championship to Philly. These are the NBA stories most told about Williams. But 13 years earlier, he bagged his first NBA GM job in perhaps the worst spot in the NBA.

“In Chicago, ‘sports’ meant the Bears, the Black Hawks, the Cubbies and the Sox, period,” Williams wrote. “The Bulls were nowhere.”

The ‘69 Bulls were a third-year franchise and the third NBA franchise in Chicago. There was no guarantee of a fourth in either. The Bulls made the playoffs in each of their first two seasons. They missed in 1969. One home game drew just 741 fans.

The team’s ownership was growing wary of team founder and GM Dick Klein. Bulls co-owner Phil Frye had heard stories of a young man running promotions for the 76ers who had previously made headlines as a minor league baseball executive. Frye asked his friend Bill Veeck what he knew about the young Sixers promoter. Veeck was Williams’s mentor; his endorsement went a long way. Soon enough, Williams replaced Klein as Bulls GM.

“What I have to offer is hard work, enthusiasm and an open mind,” the 29-year-old Williams said at his introductory press conference. “We have no way to go but up.”

So, right: Victor. The wrestling bear would put butts in seats. Wins would too. Williams brought both. In the summer of ‘69, Williams’s 76ers were attempting to acquire Bulls forward Jim Washington in a deal for Chet Walker4. When Frye connected with Williams about becoming Bulls GM, Sixers owner Irv Kosloff let his young promotions guru go because he knew that Williams could then close the Walker-Washington deal. Which he did. Promptly. In three days.

The Bulls now had access to the most eager, imaginative sports promoter this side of Veeck. He would build a winner on the court and an entertainment bonanza during the timeouts. Let’s start with the timeouts. In minor league baseball in Miami and South Carolina, and then with the 76ers, Williams became known for putting on a show: a skydiver bringing the baseball to the ballpark, or people wrestling alligators, or a performance by baseball star Dick Allen’s singing group5.

“I’d be a fool to say you can make dramatic progress by promoting an out-and-out loser,” Williams said after his first season here. “But with a team that just competes, if you have a constant philosophy of promotion, you can do a lot.”

In the 1960s, Chicago was known as “a basketball graveyard.” Williams needed a symbol of joy and fun.

He dreamed up the answer: a mascot. A fellow 29-year-old Bulls enthusiast named F. Landey Patton who worked in real estate told Williams he would love to help the club in any way possible. Williams summoned Patton to a luncheon for season ticket holders.

“We need you to put on this costume and run around the luncheon as the bull,’” Williams recalled telling Patton6. “It’s probably not what he had in mind.”

Benny the Bull was a hit with the kids7. The Bulls were a hit with the parents. By January of 1970, newspapers were reporting that the Bulls were averaging 10,000 fans a game.

“Attendance was up, but not that much,” wrote a dubious Bob Logan, the Tribune’s Bulls scribe8. “I downplayed such (attendance figure) finagling in my 1969-70 dispatches from the Bull front, since the revival on and off the floor was a more important development.”

“The first and most important step was to assure the fans we were going to stay,” Williams later told Logan9. “Then, because I knew the relationship with the coach was vital, we gave Dick Motta a new three-year contract.”

Dick Klein had hired the surly Motta for the ‘69 season and Williams empowered him. Motta ran the team and Williams ran the show. Fans viewed Williams as their friendly neighborhood basketball promoter.

And yet…

“I’ve been accused of being more interested in the halftime show than the game,” Williams said early in his first year running the Bulls. “But when we lose, I’ve been known to kick a dog or beat an old lady.”

That might seem tongue-in-cheek for a carnival chief, but Williams had a side that fans didn’t see. As Logan described “The real Pat Williams”:

“Tense, a stickler for details, he’d stand at courtside during halftime, snapping orders while trying to gauge the crowd reaction. It was a show in itself, but that side of him seldom went on public display. Always fashionably dressed in the latest with-it style, he stationed himself at a Stadium exit while the fans trooped out, complete with drip-dry smile, to dispense ‘Y’all come back soon’ chatter.”

Whether with fans, players, coaches, owners or the press, where Williams soared was his dealings with people. When Motta came to the Bulls, he took an immediate disliking to their lead scout, a young go-getter named Jerry Krause. Williams knew how to talk to both of them. He liked Krause, and nicknamed him “The Sleuth.”

“(Williams and Motta), along with Scout Jerry Krause,” the Tribune noted, “have reached the logical conclusion that the slow, listless Bull teams of the last few seasons must be brought to life if the franchise is to survive.”

They did. Dick Klein brought in Jerry Sloan and Bob Love, Pat Williams brought in Chet, traded away guard Norm Van Lier and two years later acknowledged his mistake and traded for Norm. Klein hired Motta, Williams extended him and Motta molded the first consistent winner in Chicago pro basketball. The Bulls changed ownership in 1972 but stayed in Chicago, a key moment for a formerly wayward franchise. The club had something going and new owner Arthur Wirtz, owner of Chicago Stadium and the Black Hawks, knew that whatever that something was, well, it belonged in Chicago.

In 1973, Williams lost a power struggle with Motta and left the Bulls. But that mattered more for the Bulls than for Williams, a man of reinvention and perpetual motion who always had a hand in his own destiny. After one year running the Atlanta Hawks, Williams took over the 25-57 76ers. They won 34 games his first year, 46 his second, added Dr. J from the ashes of the ABA and won 50 games and nearly a championship in his third season. Under Williams, the Sixers went to the Finals again in 1980 and 1982, losing both times to the Lakers.

When Williams added Moses and his Sixers ripped off a championship season for the ages in ‘83, the Bulls were puttering along in Chicago. What mattered was that their puttering was in Chicago. Jerry Reinsdorf bought the team in ‘84, MJ arrived, Williams left the 76ers after 1986, the Bulls became the hottest ticket in town and Williams set his sights on a new goal: bringing an NBA franchise to Orlando.

He did. He turned the Magic into a show and then he turned them into a team. He won the 1992 draft lottery, made the obvious move with Shaq, won the 1993 draft lottery and made the non-obvious move to trade Chris Webber for Penny Hardaway and three first-round picks. When a Magic executive asked him how he got the Warriors to give up three first-round picks, he said it was easy — he asked for six.

Williams kept moving. He built another Finals team, left the Orlando GM job after getting swept by, of all teams, the Bulls, stayed on as an executive and continued to create. He had life’s blueprints. His purpose was to share them. A man of deep faith and a devotion to Jesus Christ, Williams wrote over 100 books, ran close to 60 marathons and was a father to 19 kids, 14 adopted10. He finally retired from the Magic in 2019.

Through it all, he told stories. I recently connected with Matt Flesch, director of the brilliant “Last Comiskey.” Matt is now working on a documentary about Chicago Stadium, and I am working with him on the Bulls portion. I had never reached out to Pat Williams for an interview, and it dawned on me: no one can talk about the Old Barn like Williams!

I googled him last month and found his website, PatWilliams.com. I looked for the contact email. Surely I would find a contact box where I entered my information and hoped for a response. Perhaps at best, there would be something that said, “To learn more about Pat Williams, contact us at info@patwilliams.com.”

Nope.

Pat Williams’s email was pwilliams@patwilliams.com, and Pat Williams ran Pat Williams’s email. I emailed him June 11 and introduced myself, telling him that Matt and I wanted to interview him for Matt’s movie and my book. I gave him the full rundown of what we wanted to talk about: one hour on the history of the Bulls, the story of how he built a winner on the floor and a favorite at the ticket window.

He wrote back two days later.

“Jack, I would love to talk with you about the Bulls. I am traveling today and tomorrow, but am available to talk next week. Please call me … so we can set up a time. I look forward to meeting and speaking with you. Pat Williams.”

We worked on finding a date, talking on the phone one time between emails about our projects and my interest in those early days of the Bulls. He was warm and excited, eager to reminisce. But while we were scheduling, after uncharacteristically not hearing back from him for a few days, I received an email from his wife Ruth. Pat was in the hospital with pneumonia.

“So sorry he missed your call,” Mrs. Williams wrote. “Hopefully you will be able to reschedule when he is better.”

This was an incredibly thoughtful act from Mrs. Williams at an uncertain time for her and her family. I was a stranger to her and basically a stranger to Pat. But someone had reached out to him to talk, and that’s what he was going to do. Right up until he passed away, Pat Williams was in the business of sharing knowledge and wisdom, bequeathing it to whoever was ready.

“The word ‘promoter’ insinuates shadyism,” Williams said in 1970. “I hope my epitaph is written that I go down for more than wrestling bear acts and Richie Allen singing.”

From Bulls fans everywhere, you did indeed, sir. You did indeed.

-

-

-

Matt Flesch and I extend our condolences to Ruth and the entire Williams family. Thank you to Pat Williams for answering my email and getting on board for our projects. Rest in peace.

1969 was the only season that the Hawks missed the playoffs between 1958 and 1998.

The Magic of Team Work: Proven Principles for Building a Winning Team, 1997, page 28

I just love watching Pat realize the Magic just won the draft lottery for a second straight year.

For more on Chet Walker, read my tribute following his death in June: “Chet Walker: A Man of Impact”

The great Sam Smith penned this ode to Williams in 2012.

A great picture of an unmasked Benny the Bull, with Patton in the costume.

The Bulls and Chicago: A Stormy Affair, by Bob Logan, 1975, pages 113-114

Logan, page 115

The first time I learned the name Pat Williams was when he drafted Shaq, but the first time I got to know Pat Williams the person was this 1993 Sports Illustrated feature on his family. There was a great photo that took up two pages of the entire Williams clan jumping into the family swimming pool. Unfortunately S.I.’s website doesn’t show the magazine layout anymore.