Million Dollar Shot, Million Dollar Doc

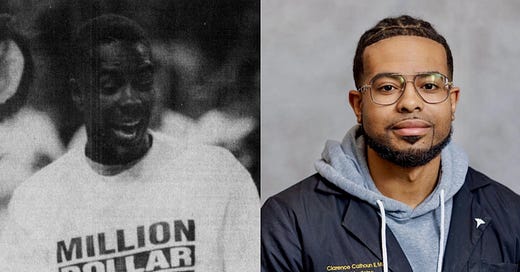

On April 14, 1993, Don Calhoun entered Chicago lore with the "Million Dollar Shot." 30 years later, his son is building on his dreams — and the legacy of his late brother.

Before The Shot splashed through, before a legend was born, Don Calhoun’s arms were already raised. He, and only he, knew this shot was going in. This million dollar shot. He was 23 with nothing to lose, his heart filled with love for Clarence. Both of them. His older brother, and his first-born son he named after him.

That son, Clarence Calhoun II, was just three years old that spring day in 1993. Don wanted to give him the world. All parents do. He would give Clarence his passion for the power of education. But what else?

He knew what else. Some of this million dollars he was about to win — that’s what else. Michael Jordan would say postgame that he had “a tough time making three free throws just because I was thinking about the guy,” but Don had no such trouble. As he stepped to one free throw line and prepared to launch a shot to the opposite basket, he was at peace. He knew how all this was going to play out.

After all, of the 18,676 fans who showed up to Chicago Stadium on April 14, 1993, he was chosen. Nineteen fans in prior games had taken The Shot and missed. Only one had even hit the rim. Later, when he was a new celebrity, he attempted to recreate the shot for Dateline with Jane Pauley. He missed his first 53 attempts and hit the 54th.

But those were for TV. This was for life. He waited for his shot, and at last, in the 3rd quarter, when the visiting Miami Heat called timeout after Grant Long was ejected following his second technical foul, a Stadium employee brought Don to the court for the Lettuce Entertain You / Coca-Cola Million Dollar Shot. Ray Clay prepped the crowd.

Don eyed that rim some 75 feet away. To his left, the Bulls bench. The players watching. Michael Jordan, keeping an eye. Horace Grant, rapt. The Stadium employee handed him the basketball. He took it without looking away from the rim. His body in action. He took one dribble. Three steps. A baseball-style throw. Everyone at the sold-out Chicago Stadium watching. Their eyes fixed on Don Calhoun of Bloomington, Illinois.

“This is on Clarence’s everything,” he thought as he released the shot.

As the ball sailed, with Clarence and Clarence on his mind, he knew what was about to happen. Saw it dropping in before the crowd did. Saw the ball’s victorious descent. Threw his arms up. The field goal sign. “It’s good.”

An instant earlier he was just another member of fandom’s anonymous ranks. An instant later he was getting high-fives and back slaps from Michael Jordan and the greatest sports team on Earth. But for just one moment, he was alone in his certitude. The shot, not yet home, was settled.

“I knew God was with me,” Don, 53, says now. “And I knew my brother,” he adds. “If they can be with you, he was with me.”

“He was my hero.” The life and death of the first Clarence Calhoun

When he had become a hero, a myth, a celebrity, the papers called him a “Bloomington Man.” And he was. But Don Calhoun started out on the west side of Chicago. Roosevelt and Pulaski. Shopping on Madison Street. Passing Chicago Stadium without ever going in. His grandmother lived in Bloomington, and when he was about 11 his family moved there.

And while this was a decision his parents made, his son sees another catalyst for the Calhoun family: Clarence.

“He was kind of the guy who had the dream early on,” Clarence Calhoun II, 33, says now about Clarence, his uncle and namesake. “He was the oldest. … And it seemed like he had the vision to change the dynamics of the family.”

When Clarence Calhoun II looks back at the uncle he never knew, he sees that vision. Clarence Calhoun was smart. Driven. Wanted to be a lawyer. Don was a few years younger than his brother. When he looked at Clarence he saw the world. They sang together in a family gospel quartet, performing at churches and even on the radio.

And they hooped. Like brothers do, they battled each other. Like brothers do, they battled together. A powerful guard, Clarence lettered at Bloomington High School and started his collegiate journey at Southern Illinois. He transferred to Triton Community College in River Grove, Illinois, and then transferred home to DePaul in 1987, where he majored in criminal justice and walked onto the basketball team.

That brought showdowns in practice with three-time All-American point guard Rod Strickland.

“My brother was coming home telling me he was killing Rod Strickland and was going to be starting,” Don says. “I know people say, ‘I know how good Rod Strickland was,’ but my brother — he was good. Man, he was phenomenal. His basketball skills, his shooting skills. He was my hero. He was everything.”

Iron sharpens iron; Clarence was Don’s. He was a senior at Bloomington High School when Clarence was at DePaul, and he knew. He just knew. Clarence was heading for a life they write about.

“Bro was gonna go pro,” Don says. “Bro was flamboyant. He was like a Mayweather. He was very confident in what he did and how he did it. He told you and everybody knew it.”

When you lose someone, you know: There is a personal tinge to death. An element that makes each transition a unique heartbreak. It’s not just the hole in your life. It’s your knowledge of what made that person special, the context that tells you and a chosen few others: all deaths are sad, but this death was particularly cruel.

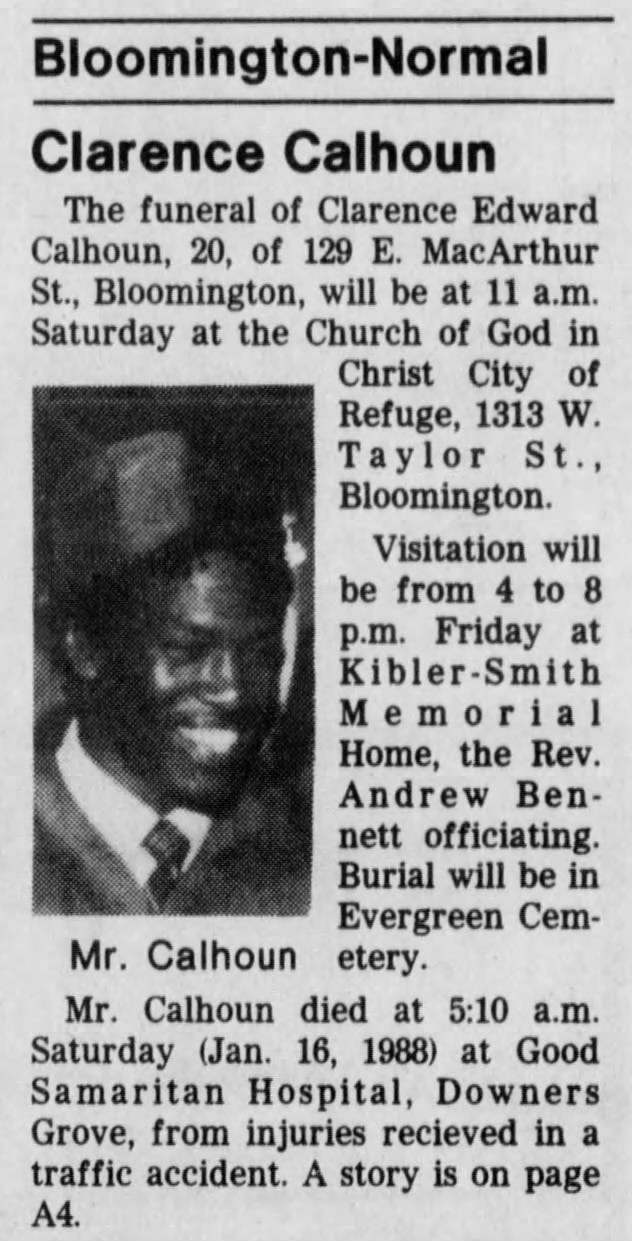

For Don Calhoun, that unique tragedy came January 16, 1988. His brother, his hero, was driving from Chicago to Bloomington to spend the Martin Luther King Day weekend home with his family. In the early hours of Saturday the 16th, Clarence pulled his car over to the shoulder of I-55, about a half mile south of Lemont Road. A drunk driver struck his car at 4:15 a.m. Clarence Calhoun died less than an hour later, at Good Samaritan Hospital in Downers Grove.

He was 20 years old.

“Lots of pain when I lost my brother,” Don says now. “To see him trying to rise and then just fall. It’s one of those stories where a kid has all this talent and it’s cut short. So I had to live a lot of my life after he passed. … I felt like I had no outlet or opportunity to have people hear me.”

The outlet wasn’t basketball, per se. The outlet was Clarence. The outlet was that drive inside the Calhouns. Don was signed up to enter the Marines following high school. His brother’s death changed that.

I’m going to go to college, Don thought as his high school days wound down. I’m going to fulfill my brother’s dreams. I’m gonna play ball.

And beyond ball:

I’m not going to let these people stop me.

“It wasn’t about basketball,” he says now. “It was about saying that no one can tell me that I can’t do basketball. It could have been soccer. It could have been a book club. It could have been anything.”

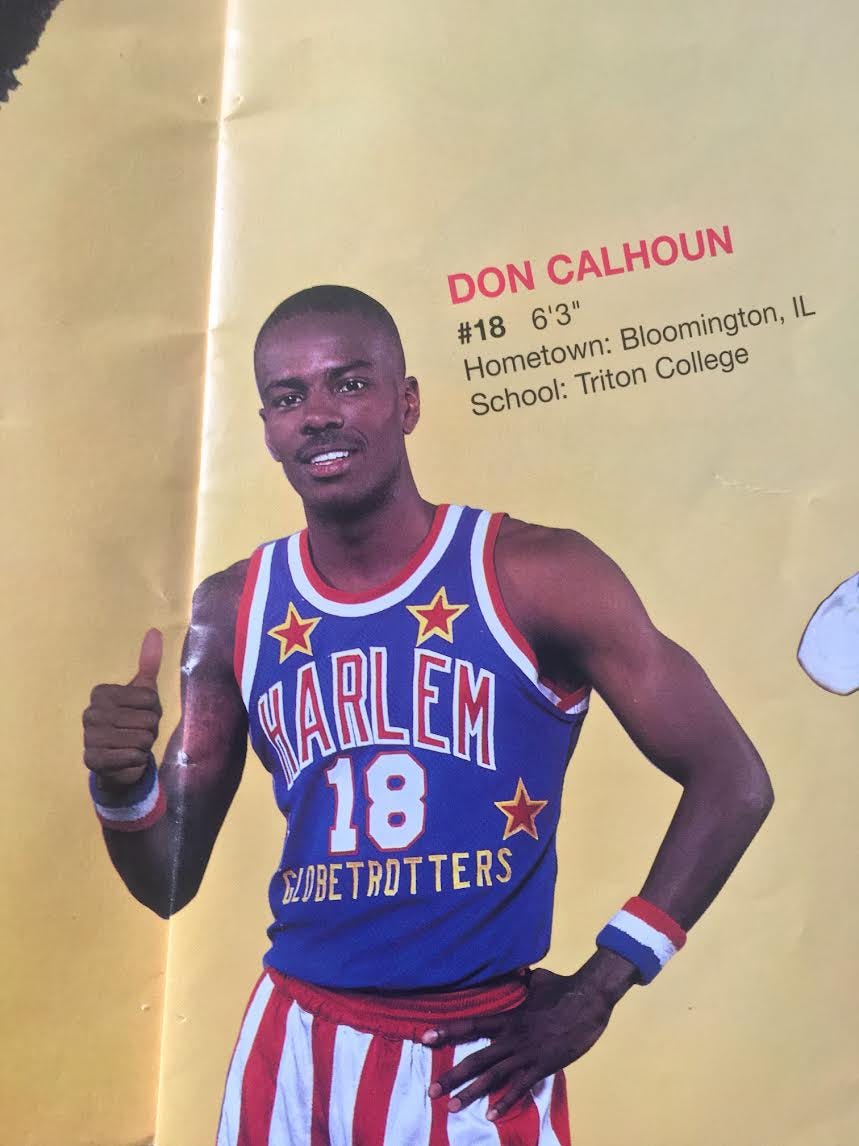

Off he went to follow his brother. Literally. Triton Community College. A walk-on. He played 11 games there. In 1993, that experience would become the fulcrum of a national debate. But not yet. When he was out there, it was just basketball. Chasing Clarence. Honoring Clarence.

He couldn’t break through in college or the pros and took an office supplies sales job for $3.25 an hour. No matter. Basketball lives on the court. That one. The one you’re on right now. At community college and then in community center games with the YMCA, Don Calhoun competed. That’s what you do when you’re a Calhoun. Compete.

In his old neighborhood, the Bulls competed too. Clarence had told Don that Michael Jordan was going to be special. Then came an NBA championship. And another. On top of the world. Don had only seen him once, when he was just 16 or 17. His bible study got Bulls tickets and he went. Sat way up high. The very top row. The jumbotron at Chicago Stadium only offered pixelated graphics, not game action. You sat that high at the Old Barn and all you could identify on the court was the dominant blur.

“It made Michael even more mysterious seeing him that far away the first time I had a chance to watch him play,” Don says.

He was closer the second time. April 14, 1993. A friend from the Y — (“Dave Deneen” he says, spelling the last name to get the record straight) — gave him and another friend tickets. When they arrived, two women working the game pulled them aside. “Do you want to take the Million Dollar Shot tonight?” they asked Don. Hearing “the shot” intrigued him.

Still, his instinct was to get to his seat. Clarence said he had to. When you go to an NBA game, his big brother had told him, don’t miss the tip.

“I was trying to live by that,” he says. “But they literally begged me and stopped me to take the shot. They were like, ‘We like your shoes. They won’t scuff up the floor.’ I was like, ‘Okay.’ They said, ‘Just sign this waiver here — this will get you to the floor at halftime.’” He signed, and he and his friend Lenny went to their seats about 20 rows behind the very basket he would soon stand under.

So no, Don wasn’t thinking much about The Shot. Not just yet. But his Spider-sense was tingling that day. When he and Lenny arrived at the game, Lenny was going to buy them beers. Don declined.

Now he sat in his seat. He soaked in the Stadium. He felt a calm. Deep focus. Chicago Stadium, he thought. I’m going to go to the floor.

“I’m thinking, ‘Man, you know what? I’m going to make this shot,’” he says now. “This is no accident right here. I’m thinking that. This is no accident.”

He’s an opportunist. That’s the word he uses. Meaning always ready for the opportunity. He learned that from Clarence. What if he hadn’t worn those shoes that day? The gold, suede, size-13 World Cup Gangsters from Kinney Shoes. What if he’d worn something else? What if he’d said yes to Lenny and had a drink at the game? What 23-year-old with his friend wouldn’t?

“I liked drinking beer at that time, and I knew not to have any beer,” Don says. “My buddy was like, ‘Hey, let’s get a beer.’ And I was like, ‘No man. This is Chicago Stadium. Anything can happen.’”

“Meeting you is an honor, Mr. President.” The legacy of The Shot.

Clarence Calhoun II remembers The Shot. His father had told him to watch for him. “Look for me in the crowd,” he said before he left. Little Clarence did. When the Stadium employee brought his father to the court, the vision was real.

“Dad’s on TV!” he shouted to his mother, Amy Bell, who was in the kitchen. His mother waved him off in that classic parental way, one of those, “Of course you do, sweetie” that parents say 1,000 times a day.

“Then she came over and saw what was going on,” Clarence, now 33, says.

While Don wasn’t surprised — (“My son will tell you, it doesn’t matter where anything is at. If it has a cup on it, I can throw it across the room and make it.”) — his family was. When The Shot splashed through, Don’s mother was at a Bible study at Bloomington’s City of Refuge Church of God in Christ, while Don’s father, Homer, had just returned home at 8:30 p.m. after his janitorial shift.

“I sat down and turned on the TV and the phone rang and my (other) son said to turn to Channel 9,” Homer Calhoun told Bloomington’s Pantagraph newspaper that night. “I saw them all hugging Don and they had a million-dollar check. Boy, I’d like to have fallen out of my chair. My wife just screamed when she got home.”

Clarence II and Amy Bell screamed too. “And that’s about as far as I can remember,” Clarence says now. “A lot of changes after that.”

The changes were immediate. In the midst of an otherwise forgettable regular season win for the Bulls (their 54th win of the season), suddenly they had a new hero. Don received a giant novelty check. He kept the ball. He gave interview after interview on the court, just missing a conversation with Michael Jordan, who waited for this Bloomington Man until he couldn’t wait any longer.

NBC put Don up at the Sheraton that night. The next morning he did a remote interview with Bryant Gumbel. When he got home, his lawn was covered with news vans. (“We don’t have those in Bloomington.”) His answering machine was filled with messages. He could barely keep up with them.

He had three keepsakes from The Shot. The first were his famous shoes. The second was the t-shirt that said ‘MILLION DOLLAR SHOT,’ which was taken from him years later in a mugging.

The third though.

The third was maybe most important of all: the ball.

He got it signed by Bulls players (including MJ, a few years later) and even two members of the Heat. Miami swingman Steve Smith would play 14 NBA seasons, reach an All-Star team, make the cover of Sports Illustrated for guarding Michael Jordan in a playoff series and win a championship with the Spurs.

But on April 14, 1993, Smith was only in his second season and Don Calhoun’s shot was one of the most exciting things he’d ever seen in the NBA. Smith signed the ball and then joyously wrote, “I Was There!”

In the coming months, Don Calhoun was there too. “There” being everywhere. He was going to Bulls games without tickets, parking at gate 3 1/2. He was a guest on Leno and Oprah. He joined the Harlem Globetrotters. He was the subject of a country song, “The Ballad of Don Calhoun,” written and recorded by two Bloomington residents.

“He said he had, ‘So many people calling me, I couldn’t tell what was real and what was fake,’” Clarence says. “To just kind of look back, that’s a big change to undergo from where his family’s from in Chicago to something like that.”

“Something like that” even included an invitation to the White House. Him! Bloomington’s own Don Calhoun. President Clinton invited him for the National Sports Awards at Constitution Hall. Don’s fellow recipients that day included Muhammad Ali, Kareem Abdul-Jabbar and Arnold Palmer. Wow, the President, he thought as Clinton appeared while he and those other sports stars stood in the receiving line.

“I am Don Calhoun,” Don said as he shook hands with the President. “Meeting you is an honor, Mr. President.”

“Don, it is an honor to have you at the White House,” Clinton replied.

“The Ballad of Don Calhoun” by Bones Bach and Steve Vogel:

Clarence II did not come to the White House. He went plenty of other places, that’s for sure.

“I was so young, so the stuff that I remember is probably different than what actually happened,” he says now. “I just remember a lot of people being at our house. I remember going with him a lot of places. He played for the Harlem Globetrotters and I just remember sitting on the floor during Globetrotter games. … I remember coming out at halftime with Globie, doing the halftime show with them. … I remember going to a Toronto Raptors game. I think I was about 8 or 9. I sat on the floor, right next to the bench. Those are the good things that I remember.”

He also remembers his father bringing his newfound celebrity home to Bloomington. Don rented the gym at Bloomington High School and hosted The Million Dollar Man Basketball Clinic for boys and girls, 4th grade to 12th grade.

“To this day, everybody I know talks about the camp,” Clarence says. “I think everybody in town went to this camp. He brought NBA stars in. I think that was good for the neighborhood to see that.”

That’s what Don wanted. To re-gift the joy he heard when he hit The Shot.

“It was just a roar at a low decibel — it went on forever,” he says. “They say it was louder than a Game 7. It was loud. And the roars were all connected.”

He continues, and you can hear his smile.

“People were so happy, man. And that made me happy — that people got joy and not resentment. That was the medicine that it carried. A lot of resentment came later, but for the initial shot and the excitement of it, it brought joy to a lot of people and I liked that.”

In the days that followed, much was made as to whether the insurance company that insured the event would pay out. Eventually they did: $50,000 a year for 20 years. Immediately, he had three plans for that money.

“My brother didn’t have a tombstone,” Don says. “That was the first thing I bought: a tombstone.”

The second: re-invest in his own education at Heartland Community College, where he was studying business law.

His third plan for the money, as reported in the Sydney Morning Herald in Sydney, Australia, of all places: to “salt more money away to ensure a college education for his three-year-old son, Clarence.”

“A young guy.” The eternal mentorship of Dr. Valentyn Siniak

“You are the captain of what you want to do,” Don would tell his children, including Clarence.

“I have four kids — two boys, two girls — and my kids were everything to me,” Don says. “That’s my family. That’s my team. So I always had a conscious mind that I didn’t want to spend time in prison. I didn’t want to spend my life doing bad stuff, making bad decisions around bad people. And I told that to my son at an early age. Because it’s hard raising Black boys. We’re all susceptible to gangs. And I had to teach him how to follow his own mind.”

“He pushed for me to go the education route as opposed to other routes in life that other family members went,” Clarence says. “I think he was definitely the one who was a lot more woke out of his siblings, to give a viewpoint to how important it is to have a dream and pursue that. I think that was super useful to be under his wing and learn little tricks about life. That gave me confidence early on.”

His dream initially was to be a mechanic. “But he put a little more pressure on me,” Clarence says. “‘You can always do that. You can always play ball. You can always be a sports fanatic and pick up a trade. But what else can you do?’”

Clarence wasn’t sure. He attended Wiley College in Marshall, Texas, planning to play basketball like his father and uncle. A guard, like them. But his grades were low and he had to sit out a year. That’s when he met another man who would change his life. A professor: Dr. Valentyn Siniak.

“Today is his birthday, too, crazy enough,” Clarence says, telling his story. “He was a medical doctor from Russia. He worked with me, he encouraged me. I started studying.”

Medicine, Siniak told him. Clarence listened.

“It wasn’t like I wasn’t smart, but I never tried to study and get all As,” Clarence says. “After I met him, my grades shot up. My first year in college, it was Cs and Ds and Fs. After I met him and started tutoring, I jumped up to As and Bs, and then straight As. I finally got that confidence: I want to be a medical doctor.”

And then, death’s personal tinge. Dr. Siniak, just 37, dead in a motorcycle accident.

“A young guy,” Clarence says.

Clarence’s shift to medicine was a joy to Don. The Shot had paid off: he would contribute to Clarence’s medical school expenses.

“Medical school is super expensive, and he helped out,” Clarence says. “The loans pile up. And where we come from, there’s not much help outside of that.”

“Clarence has had a non-traditional background leading to being a physician,” says Dr. Min Joo, critical care physician and pulmonary physician at UIC, and a key mentor for Clarence. “He’s not from a line of physicians. He hasn’t had a lot of advice from people along the way on how to find his way to being a physician. He’s had to do that all on his own. We related, to that extent. Because I am also a first-generation physician. … I think that makes him a stronger physician, because he has a better understanding of what our population at UIC and Jesse Brown are experiencing.”

In 2021, eight years after Dr. Siniak died, 31 years after his namesake died, Clarence Calhoun II graduated from UIC. He was a doctor. His father gave him two gifts. First was two gold, size-13 World Cup shoes from Kinney’s, now signed by the man who made them famous. The second: the basketball. THE basketball. Clarence hadn’t seen it in years. When he was a boy, the ball was just around the house. “I used to dribble it,” he says in proud disbelief. “Then he kind of put it up for a while. I don’t know where it was for a while. And then when I graduated med school, he gave me the ball. It was something I could hold on to and keep safe.”

“He is deserving of the ball,” Don says. “He’s a champ. He’s bringing the bacon back home. He always said that he was going to try to turn into something great, and Clarence is doing that. And he came from that. That’s what his uncle was. His uncle Clarence was going to be a lawyer. So it makes sense that Clarence was going to be a doctor. His name, Clarence: that’s the name of someone who is important.”

“Hearing from my pops, and hearing in general how my uncle was and his dreams — he wanted to be a lawyer — all of that together, I knew early on that I was going after something,” Clarence says. “I didn’t know exactly what it was, but I had this energy that I’ve just been chasing for a while.”

“It shouldn’t matter what you look like, where you come from: you should get high quality care.”

Don Calhoun always knew that his oldest of four children did things his own way. He’s fueled by that drive. That Calhoun drive.

So as a hospitalist at UIC, Dr. Clarence Calhoun II, does something different every day.

He wears a black coat.

“I don’t know if you know, but the percentage of Black men in medicine is like less than 1%,” Don says. “So what he did was pretty phenomenal. It’s heritage and pride for him. He always liked to do things differently. He dresses differently. He’s trying to think on his own, outside the box. I support him.”

Dr. Calhoun is in the second year of a three-year residency at UIC. He works with patients who arrive from the ER or surgery. “We stabilize people,” he says. Confident, focused. Like his father standing at one free throw line, eyeing down a basket 75 feet away.

“He told me (his father’s) story when I first met him,” Dr. Joo says. “He’s very open that way.”

As a 4th year medical student, Clarence sought out Dr. Joo to speak with her and ask her questions about his career path. “He was very open about his overall situation, asking me questions that I thought were very motivated questions as to what he needs to succeed,” she says. “He was very interested in pulmonary and maybe critical care. What should he be doing? What advice could I give him? We had a discussion then and he continued to reach out to me.”

As all med students do, Clarence had book smarts and a growing subject matter expertise. But he had two unique elements, Dr. Joo observed.

“His first rotation was going to be in the intensive care unit,” she says. “‘What do you recommend? How can I prepare?’ He’s that type of a person. He’s very motivated.”

She saw his drive. She saw his empathy.

“To be a good physician, we have to have a level of empathy,” Dr. Joo says. “And the more you can empathize with somebody, the better doctor you’re going to be to that individual. You can look deeper into the causes of their medical condition, why they aren’t able to take their medications, or why they have barriers to do certain things. I think our life experiences contribute to being better physicians.”

That’s why he wears the black coat. It represents his determination to bring care to everyone.

“I’ve been wearing it since med school,” Clarence says. “I wanted to symbolize the way that we provide health care to patients. It shouldn’t matter what you look like, where you come from: you should get high quality care. There have been a lot of statistics that show that there are certain groups that are not getting that quality care. It’s been all done under the white coat essentially, so I kind of want to use it as a reminder or something to refresh or reinforce the fact that we’re all humans. When we’re sick, we need help, period. It shouldn’t matter about anything. So I’ve been wearing it about three years now.”

The coat turns heads. Doctors ask him about it. They like it. They respect it.

“My goal is to get more people (wearing it),” he says. “I haven’t seen anyone get the black coat yet, but there are always people interested and asking questions.”

A good doctor asks questions. A good lawyer does too. Their minds are always moving, thinking back to the people who paved the way and the ones who will benefit from their path. Dr. Clarence Calhoun thinks of his uncle. He thinks of Dr. Siniak.

He thinks of April 14, 1993.

“That shot gave me hope and gave me inspiration,” he says. “It gave me drive. When I was going against the odds with things, I felt like that was one in a million. Pops did something that was amazing. Even if I still watch it today, I’m still shocked. Wow, he swished it! All net!

“He had a lot of things going against him at that point. His brother had just died. That just gives me hope that anything is possible. I don’t feel limited to my situation or where I came from.”

He pauses.

“That’s what The Shot showed me: There is no limit.”

-

-

-

Dedicated to the memory of Jason “Gatz” Shaw. We love you brother.

Thank you to Don Calhoun and Dr. Clarence Calhoun II for their time and trust.

Salute to Ryan Hockensmith of ESPN, who published his own account this week of Don Calhoun’s story. For much more on the business side of the Million Dollar Shot, along with an incredible MJ story, check out Ryan’s story.

Awesome story. Very inspirational and well written.

Beautifully written sir!