Will Perdue had a front-row seat for the birth of the Bulls.

Make that the birth of “THE BULLS!”

“Honestly, it was that first championship where we had the thing at Grant Park,” Perdue told me. “You just look out and see all these people in Grant Park. You’re just like, ‘Holy shit.’”

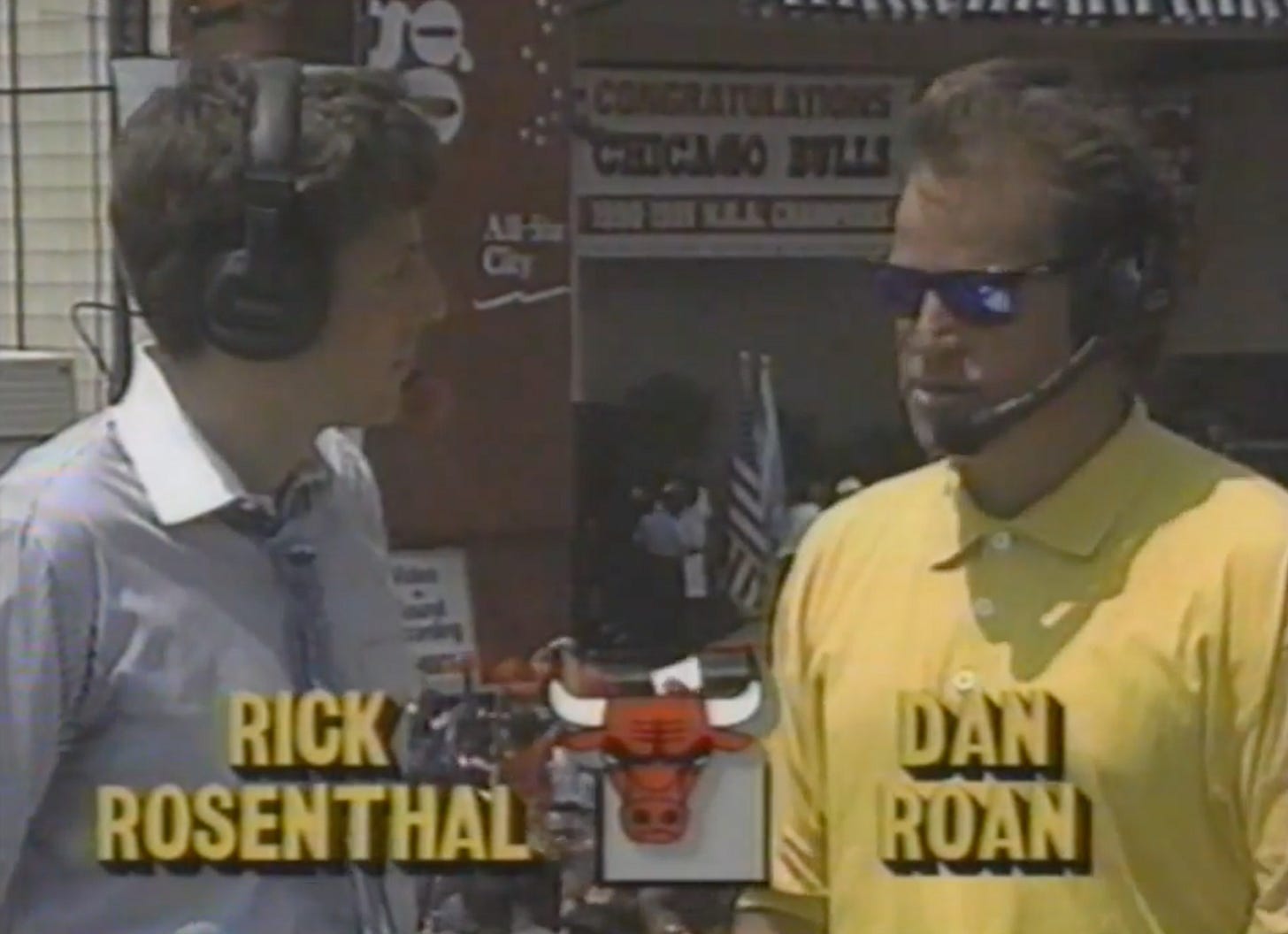

Entering 1991, the Bulls were the toughest ticket in sports — and not just at home. The consecutive sellout streak was three seasons and counting but the 1990 season saw us sell out every road game too. Getting to a Bulls game in the 1990s was a Herculean task. During the WGN broadcast of the rally, Dan Roan noted that the season ticket waitlist was “6,000 and growing.”

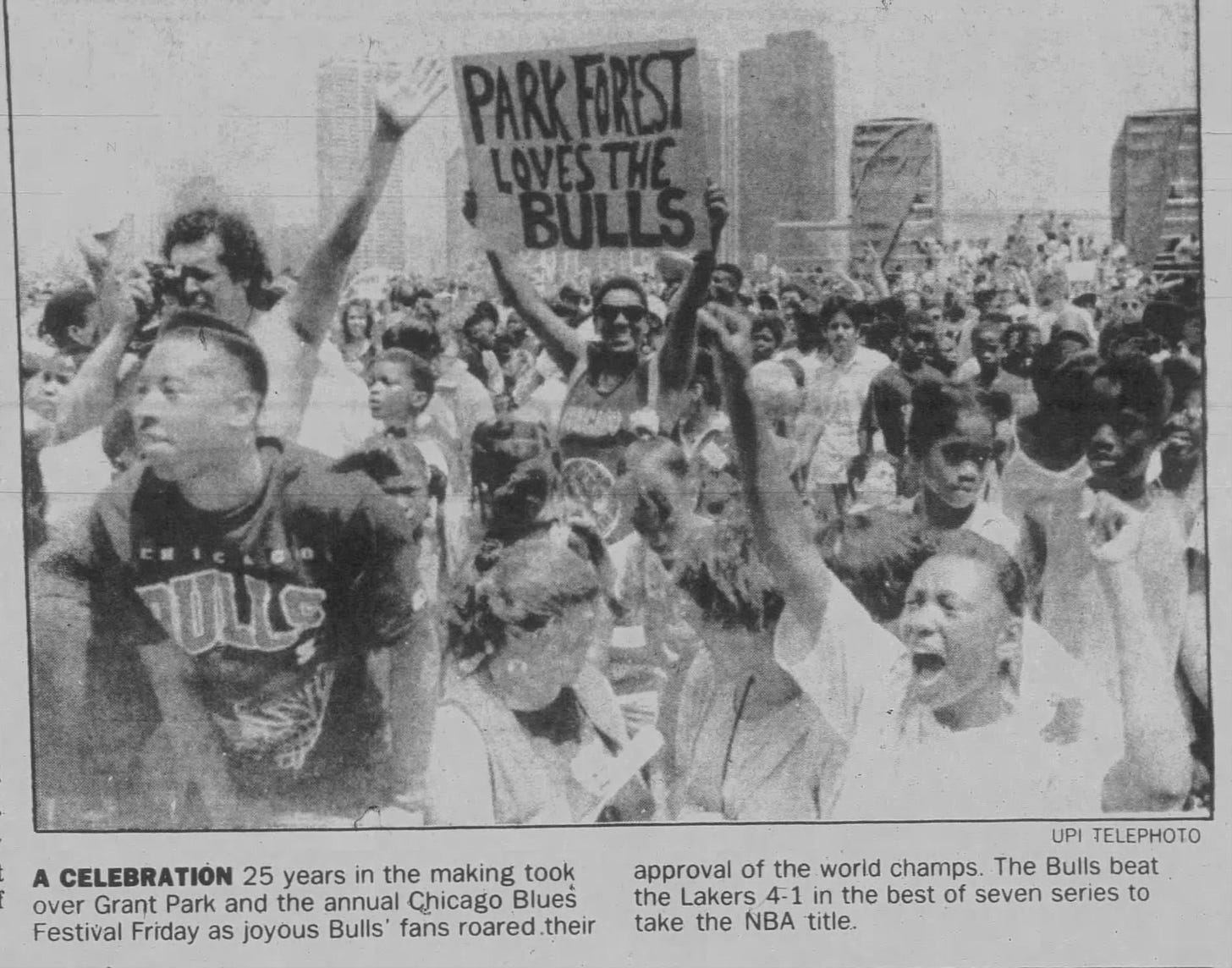

That made June 14, 1991, a new era of Bulls culture. A Bulls championship rally at Grant Park, an affair that would convene six times between 1991 and 1998, was a less expensive chance for Bulls fans to get close to their heroes.

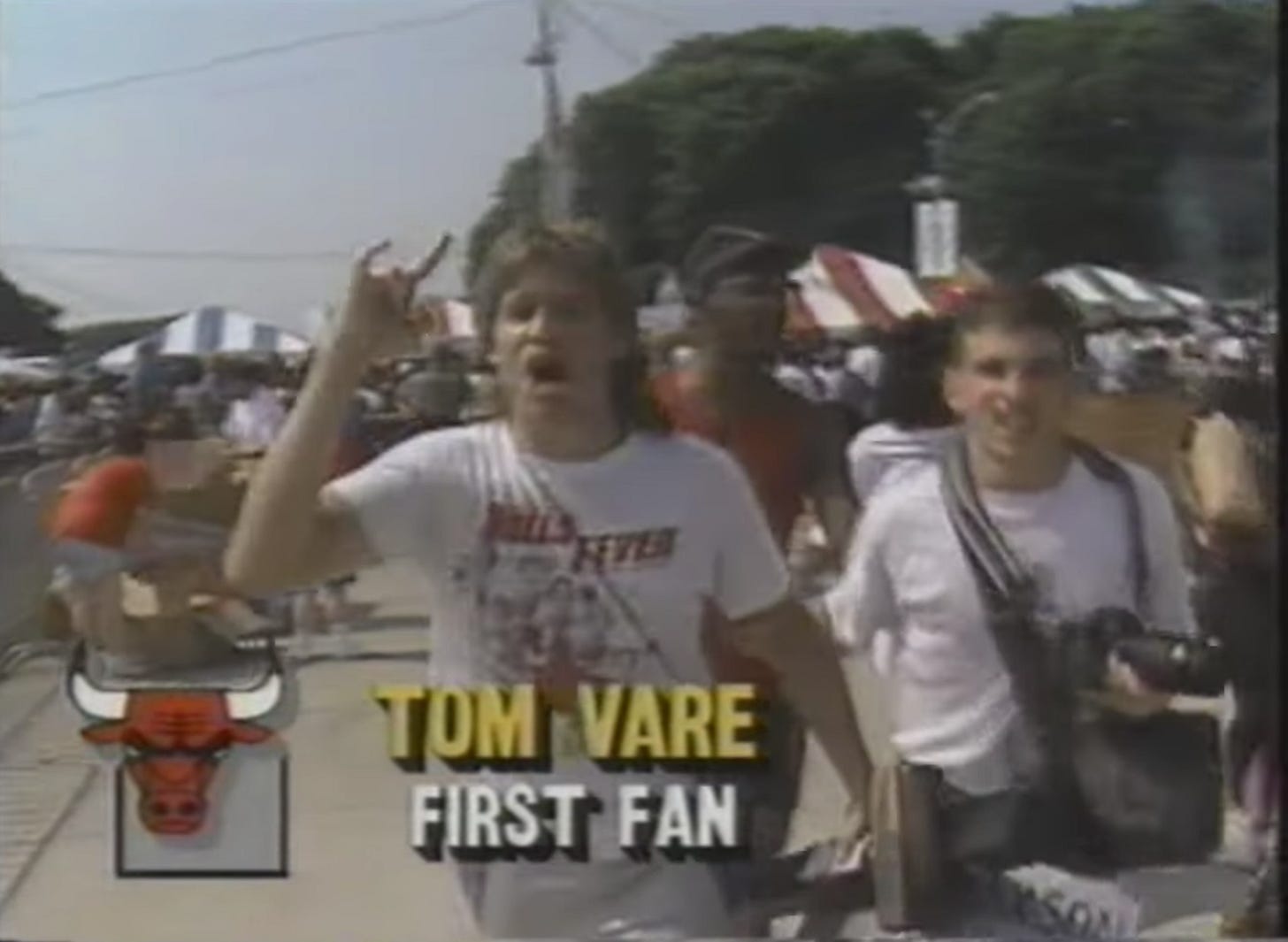

“I can’t get Bulls tickets,” said 25-year-old Tom Bare, the documented first fan to arrive for the first ever Bulls championship rally. “This is the only way to show my appreciation. I’d like to just get close to one of them.”

Bare — listed as “Vare” on WGN — came from Des Plaines, and arrived at Grant Park just before midnight. Another fan from Des Plaines, 36-year-old Ed Mueller, got to Grant Park not long after Bare. Mueller told his wife he was coming to the rally. He just didn’t say when.

“I left after the wife and kids were asleep,” Mueller told the Tribune. “This was the first time I ever slept on a city sidewalk.”1

Here are some of the stories and images from the first Bulls championship rally, along with memories from Bill Cartwright, Craig Hodges, Will Perdue and Chicago Stadium sound man Jim Irwin.

DID YOU ATTEND A GRANT PARK RALLY? Do you have photos or video from one of the rallies? Email me! 6ringsbook@gmail.com.

Thursday, June 13: City Hall announces the rally for Friday

With the Bulls leading the Finals 3-1, the debate about how to celebrate a Bulls championship was on. Mayor Daley wanted a rally at Grant Park, while aldermen Lawrence Bloom and Ed Smith pushed for a parade through their respective wards.

“The Bulls are from the West Side, they play on West Madison,” said Ald. Smith of the West Side 28th Ward. “Why shouldn’t they march down Madison Street where their neighbors — my people — live?”

Mayor Daley dismissed that concept on the basis that “you can’t have 50 celebrations” but decided that Smith and Bloom were right with their request for a parade, albeit in “a central location.”

Immediately after the Bulls won the title in Los Angeles on Wednesday, June 12, the mayor’s office announced that the city would celebrate the Bulls championship with a combination approach: parade plus rally. Bulls director of promotions and corporate sales David Brenner called Stadium sound engineer Jim Irwin Thursday morning and told him to contact Kathy Osterman at the city’s Office of Special Events.

“I told her who I was and why I was calling,” Irwin said. “She said, ‘Yes, great. Meet us Friday morning at Grant Park.’ It was a hurry-up thing because the Bulls wanted it, and that was the same weekend as the Blues Fest that they put on at Grant Park.”

Friday, June 14, rally day: setting up the stage and sound, and fans arrive

As Bare, Mueller and perhaps as many as one million Bulls fans2 awaited entry to Grant Park or made their way downtown, Jim Irwin began setting up the sound.

IRWIN: I get there and they had this makeshift stanchion thing where the people that were going to be working the Blues Fest were going to be. We were right there, right where the fence was. I had to go to the old stadium and get the music.

I got there real early that Friday morning, got it all — cassettes, carts — and brought one of our cart machines for the tape cartridges over there.

The gates opened, with Tom Bare leading the charge into the park. Allison Payne was reporting for WGN; among her interviewees seated in the Petrillo Music Shell near the stage were members of Brown Elementary School, a school walking distance from Chicago Stadium. The Tribune profiled members of the neighborhood at the start of the Finals — including students at Brown — exploring the dichotomy between life on the West Side and the global glitz and glamor occurring inside the Stadium during Bulls games.

Now, 10 days later, Payne was asking principal Shayle Gerstein how Brown Elementary ended up welcomed into the center of the American sporting world.

“The mayor picked us to represent all of the Chicago Public Schools,” Gerstein said. “The mayor came back to our school back in January and talked to our 5th graders when they had their culminating activities for D.A.R.E. We were in the Tribune last week on the front page. A reporter interviewed us.”

Payne shifted to 13-year-old student Torrence Smith. “What are you thinking about?” she asked. “I know you’re excited to see Michael Jordan.”

“Yeah. I want to see the Bulls,” he said, trailing off. Sensing his tentativeness, Payne asks what Smith would say to MJ if he could talk to him. “Well, I’d say… can I see him again?”

The motorcade chaos: the view from players in cars on Columbus Drive

Craig Hodges knew better than any of his teammates just what a championship would mean to Chicago fans. Yet even he was in awe.

“Man, it was the whole buildup to it,” the Chicago Heights native said. “The buildup of going to the practice facility, getting on the buses, having a police escort, riding down the expressway with no traffic in front of you.”

Bulls players began their morning at their Deerfield practice facility, the Multiplex, and took a bus downtown for the motorcade parade. City officials had concerns all week about the logistics of a parade, recalling the problems five and a half years earlier when Chicagoans stood outside in sub-zero temperatures for the Bears Super Bowl parade3.

That wasn’t a problem for the Bulls parade, obviously, with temperatures in the 90s. Additionally, because the Bears Super Bowl parade on LaSalle Street took place the day after the Super Bowl, the team’s nine Pro Bowlers could not attend, as they were already in Hawaii; this included Walter Payton, Jim McMahon, Mike Singletary and Super Bowl MVP Richard Dent.4

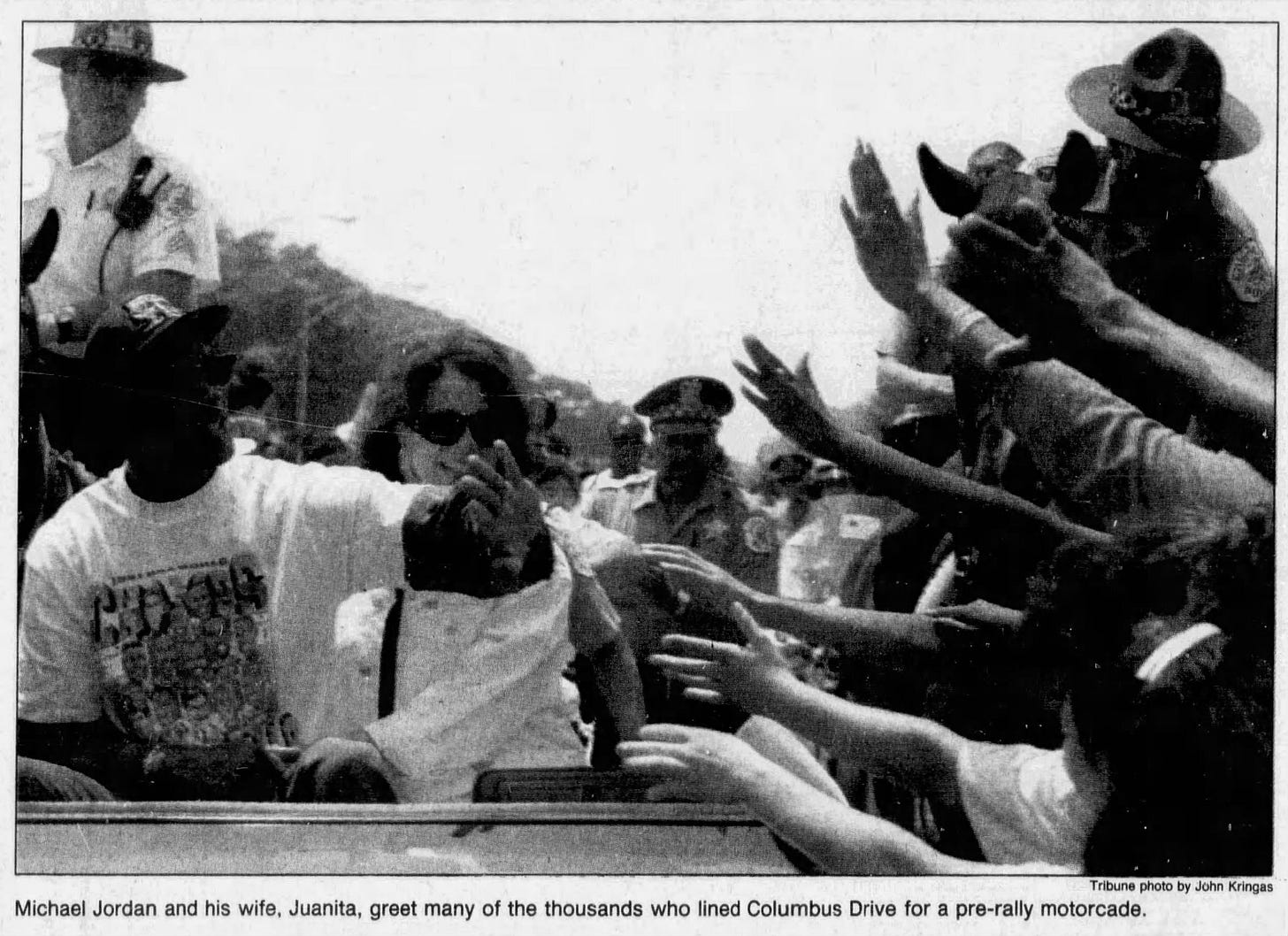

Conversely, every Bulls player was in his own car for a motorcade, including Michael Jordan. The police had barricades. The fans had passion.

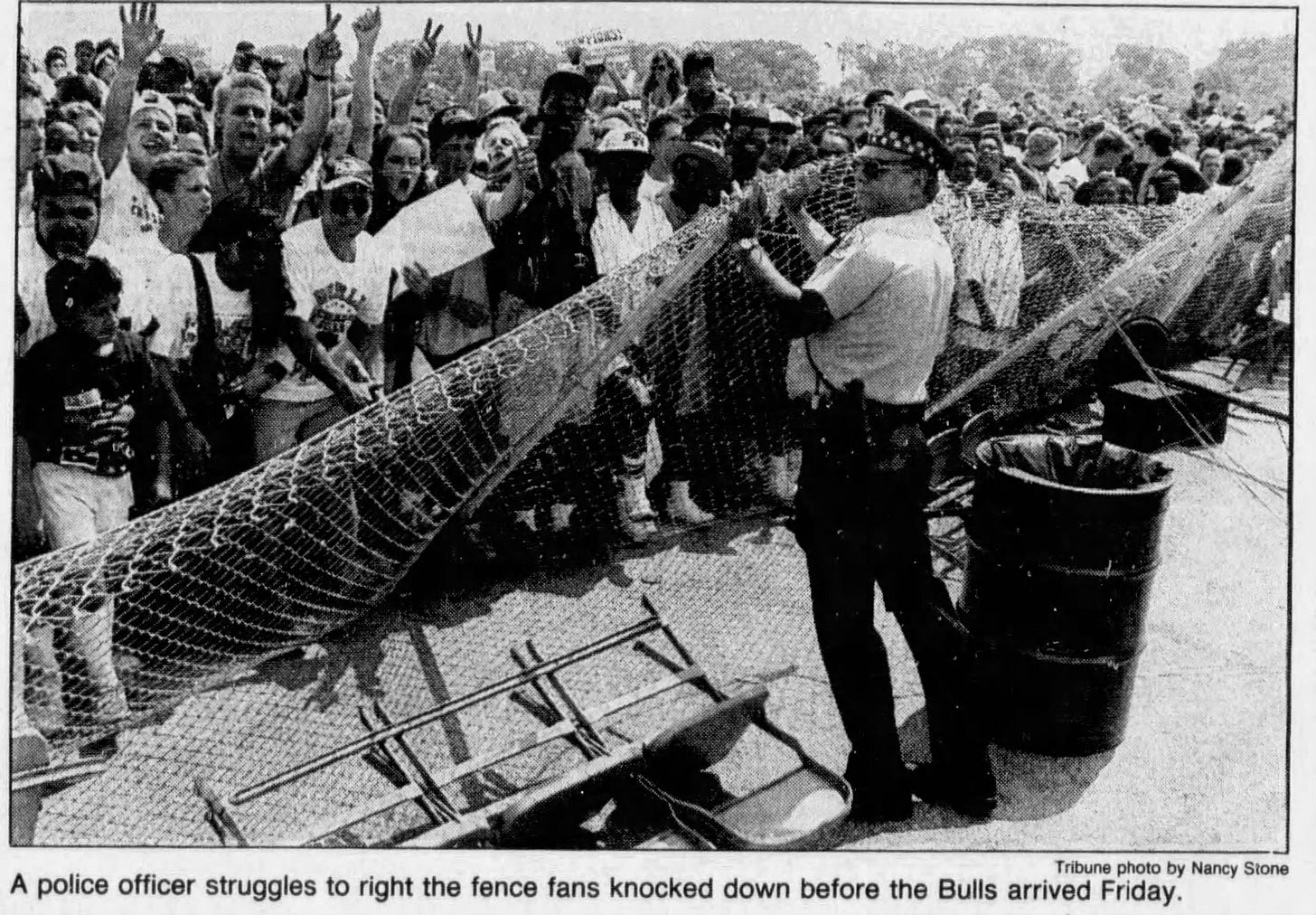

“We try to control them, but they’re just too much,” 18-year-old Jesse Bada, a Grant Park security guard, said that day.

Here’s what the parade looked like for Bulls players:

WILL PERDUE: We had a police escort, and all of the TV stations had helicopters flying above us. You’re just like, “Holy shit, what is going on here?”

CRAIG HODGES: Then to get in the little sheds where we got in the cars for the parades, and then have the barriers put up along the sidewalks. The fans tore the barriers down and now they were right up next to the cars, 10, 12, 20 deep.

WILL PERDUE: Everybody got in the car and you’re going to drive down in this convertible and wave at everybody. Your family is in the car, and all of a sudden people were just like, “Fuck it.” Knocked the barricades down and rushed to the cars.

BILL CARTWRIGHT: The fans are all around you and people are getting stepped on. Cars are on fans’ feet.

WILL PERDUE: People were high-fiving you. There were just so many people that the cops couldn't control them.

BILL CARTWRIGHT: There was this kid who wanted to shake my hand and every player — I think my wife and kids were in the car — we had our championship hats on. I reach over to shake this kid’s hand and the kid reaches over and snatches my hat off my head and runs. (Laughs.)

WILL PERDUE: You were just like, “No, this is out of hand.” You’re scared. That’s when you realize — you can say “chaos” — that’s just when you realize this thing is at a serious pitch. This is unbelievable how these people are celebrating, how they’re reacting.

CRAIG HODGES: And then how long it took us to get down the street to Grant Park. Something you could probably walk in 10 minutes took us maybe 30 minutes in the car because there were so many people.

WILL PERDUE: That was the first time I had experienced something like that. Quite honestly, it was almost more important and enjoyable to them than it was to us.

Rally time! Inside Chicago’s biggest party

Right from the get-go, the crowd was bigger than anticipated. Roan and Rick Rosenthal noted that there were 5,000 seats in the band shell area but probably 10,000 people filled that space. As Tribune sportswriter Melissa Isaacson worked the crowd, she met a woman sitting in a folding chair that police officers had given her after she had passed out, presumably from the combination of the heat, the crowd and the pure intensity of the day.

“Interview her,” one officer said. “Interview the woman who passed out but would not leave.”

“Why are you still here?” Isaacson asked. “What would possess you to come here? To stay?”

The woman’s chair was immediately in front of a wooden barrier that was being pushed from the other side by fans.

“Because I want to see Scottie Pippen,” she said in a voice that Isaacson described as “weak but defiant.” With that, the crowd surged behind her, knocked out the barrier and kicked out her chair, sending her to the ground.

“I knew this was a tragedy waiting to happen,” one officer said.

Added another: “If I wasn’t working, I wouldn’t be here in a million years.”

Certainly there was fear among some revelers, some police officers and security guards and even the players. But on a whole, the 1991 rally delivered as promised. Students from Grant Elementary School, 145 S. Campbell Ave., less than a mile west of Chicago Stadium, sang and played instruments, performing a festive anthem with lyrics “Hey - hey! The Bulls are alright!”

Then came Osterman of the mayor’s office to introduce the Chicago Stadium standards: the Bulls Brothers, followed by the Luv-a-Bulls dancing with Benny the Bull, as the fans chanted “We want the Bulls!”

Red Kerr was the day’s emcee, introducing the Calvin Bridges Gospel Singers for the national anthem, Bridges belting it out in fine style. At last, around noon, it was rally time. Johnny Red started by introducing the VIPs in this order:

Mayor Daley — booed lustily

Gov. Edgar — booed, but not quite as much

Jerry Reinsdorf — cheered

Jerry Krause, with trophy — cheered even more

Phil Jackson

With that, Jim Irwin pressed play on “Sirius.” Grant Park officially felt like a Bulls game.

“Where’s Ray Clay when we need him?” Roan said5.

Red announced the players one by one: rookie Scott Williams, then Perdue, Dennis Hopson, Cliff Levingston, Stacey King, the hometown hero Hodges, who received a thunderous applause, and sixth man B.J. Armstrong.

“You’re used to 19,000-whatever at the Stadium (so) you get lost in the game and you’re not thinking about the millions of people watching at home on TV,” Perdue said. “But at Grant Park, you’re just walking out, and you’re like, ‘Oh, my gosh.’”

“To actually walk out on stage and see people as far as you could see is something that you would love for everybody on the planet to experience,” Hodges said.

Over at his makeshift sound booth — a scaffolding about 10 feet tall — Irwin watched nervously as fans continued pushing against any barricades between them and the stage.

“We’re right in the middle, and so I’m like, ‘Man, I hope they don’t knock us over,’” Irwin said. “(The scaffolding) started moving a little. It was kind of hairy there for a bit, but eventually, people kept their composure.”

At last, the fans heard the five names they loved the most. Horace Grant was first, then Cartwright, then Game 5 hero John Paxson, then Scottie.

“That was amazing,” Cartwright said. “You walk out there and there was a sea of people … that’s something that is really special. I had never seen that before. It was amazing. I’m not even sure if you can really explain how massive that crowd was and how amazing it was to be there especially the first time.”

“Alright, fasten your seat belts,” Roan said.

“And from North Carolina,” Red started, and no one needed to hear the rest. Not Tom Bare. Not Ed Mueller. Not Torrence Smith. No one. They knew and they exploded. “The MVP,” Red said. “Michael Jordan!”

Even MJ looked giddy. We’d seen him smile in commercials, we’d seen him scowl at opponents, we’d even seen him cry on the trophy. But the Michael Jordan who walked out onto that stage looked just as astounded as the undrafted rookie Williams. MJ gave Jerry Krause a two-handed high-five, gave Jerry Reinsdorf one too. When he took the podium for his speech he clutched his hands together and giggled.

For one million Bulls fans, this was the moment they got to see their heroes.

I like to think this was the moment our heroes finally saw us.

-

-

-

Thank you to Newspapers.com, and to the reporters at Grant Park for the ‘91 rally. And a big thank you to the proprietor of Analog Indulgence, who uploaded the full rally video on youtube.

Please share this story with your best Bulls fan friends, especially if they ever hit a rally!

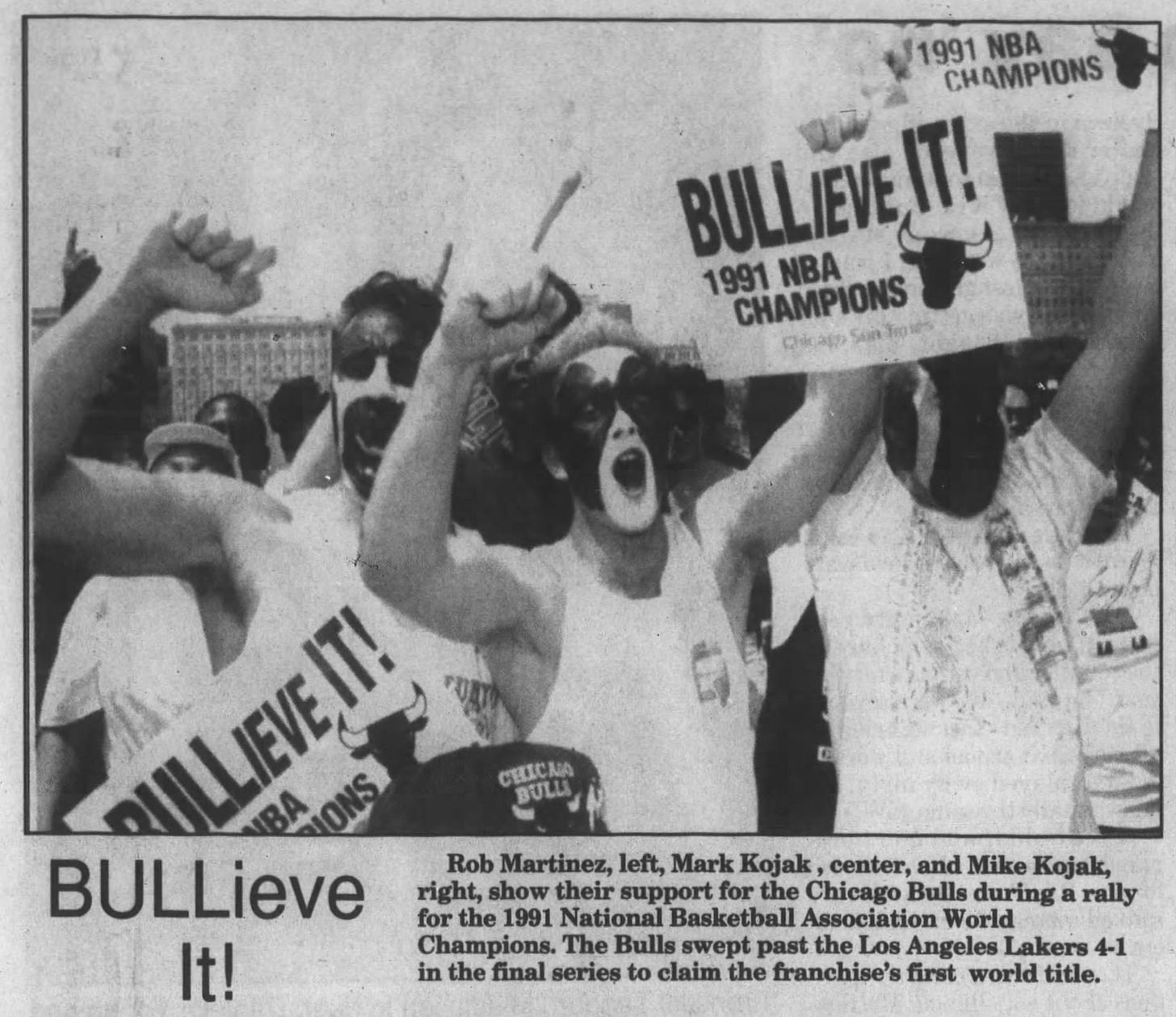

Aaaaaaand now… faces in the crowd! See anyone you know?

The stories of Bare and Mueller are from “Some ugliness mars party in Grant Park” by Melissa Isaacson, Chicago Tribune, June 15, 1991.

From the UPI, June 15, 1991: “The city estimated the crowd at one million, although many observers thought it was closer to 500,000.” The Tribune reported that CPD estimated the crowd at one million, adding: “It was comparable to the numbers who flocked to see Pope John Paul II in Grant Park in 1979.”

As reported by the Tribune, the temperature with the windchill was -25. Said Bears fan Wendy Rosiak: “I may have to have my toes amputated but I’ve got to see this parade.”

For more, here is my story on the subject in the Chicago Daily Law Bulletin, January 26, 2015