The 1991 NBA Finals Were David Stern's Godsend

The Magic vs. Michael Show forever changed Stern's NBA

“This might be so good, we can’t screw it up.”

— NBC Sports Executive Producer Terry O’Neil, on the eve of the Magic-vs.-Michael 1991 NBA Finals

Rumors of David Stern’s Machiavellian maneuvers came just five months into his tenure as NBA commissioner — and from the NBA’s soon-to-be MVP and Finals MVP, no less.

“Stern told a fan that the NBA needed a seven-game series, that the league needed the money,” Larry Bird said after Boston’s Game 6 loss to the Lakers in the 1984 NBA Finals. “When the commissioner makes a statement like that to a fan, you know it’s going to be tough.”

For 30 years under Commissioner Stern, the NBA was defined in part by suspicions like Bird’s — a sense that Stern would use the levers at his disposal (namely, the referees) to manipulate the best possible outcomes, whether a team or player matchup for fans, an extra game or two in a playoff series, or both. Stern enjoyed playing coy; in response to Bird’s comment, he pled fandom, denying Bird’s interpretation but not the comment itself.

“It’s ridiculous to draw any inappropriate conclusion from something like that,” Stern said. “I’ve been for a seven-game series all along, just like every other sports fan in America. It’s a dream matchup.”

The Lakers-Celtics rivalry of Magic Johnson and Larry Bird represented the NBA 1.0 in the Stern era. Seven years later, on the cusp of the dream matchup that would kickstart the Stern NBA 2.0, the commish offered a coy rebuke to the notion that he was rooting for the Lakers to defeat the Portland Trail Blazers and meet the Bulls in a Magic-Michael Finals.

“I’m not here to bury the Blazers — I’m here to praise them,” Stern said at Game 5 in Portland. His Mark Antony riff may have inverted Shakespeare’s famous line, but the conspiratorial undertones remain. Two nights later, the Lakers knocked out the Blazers and gave Stern and his league’s new television partner NBC the greatest gift of all: its two biggest stars in the championship series, one man representing the league’s biggest decade (thus far), the other representing a tantalizing future set to unfold.

The memory of a decade never aligns perfectly with the years that frame it. What we think of as “The Sixties” probably started with the JFK assassination, and dripped into the early 1970s. The 2000s started with 9/11 and ended with the financial crisis and Obama’s election. The 1990s actually started right on cue: the phrase “Hey, it’s the Nineties!” — a credo for loosening up and embracing MTV-style mores — was uttered pretty much as soon as the clock struck 1990.

David Stern’s 1990s NBA, one of the most successful runs any sports league has ever had, took one more year to get rolling. Like the Beatles on Sullivan, the 1991 Finals — which concluded 30 years ago this week — struck the NBA like lightning: an instant new era that wiped out everything that came before. Three of the elements that shaped the 90s NBA kicked off with the ’91 Finals.

Only the first was guaranteed.

The Best Finals Matchup $600 Million Can Buy

“It is a matchup so natural, so provocative, that basketball fans have argued it for years.” So began Marv Albert to kick off Game 1 of the ‘91 Finals — the first Finals in NBC’s first year as the official broadcast partner of the NBA. The network sealed the deal on Nov. 9, 1989, to start in the 1990-91 season, for $600 million over four years. Its trademark game introductions blended nostalgia and journalism with a theatrical flair, and were a major part of what made the NBA feel so different on NBC than it did on any other network.

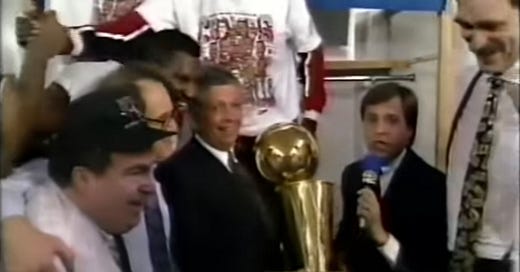

The play’s the thing, as it were, and this one had co-producers: NBA commissioner David Stern and NBC Sports president Dick Ebersol.

“They were both similarly minded in terms of how to present the NBA: it was going to be entertainment — it was going to be a show,” said NBA author Pete Croatto on a recent episode of one of my favorite sports pods right now, “Bigger Than the Game With Deremy and Jose.” Croatto was discussing his book From Hang Time to Prime Time, which chronicles the league’s rise from 1975 to 1989.

“Dick Ebersol’s approach to the NBA was that it was going to be like a series, with a beginning, a middle and an end,” Croatto said. “And that was right in David Stern’s wheelhouse. That was music to David Stern’s ears.”

The NBA rose in every conceivable way in the 1990s, from franchise value and player contracts to cultural relevance and global fandom. So much of that growth began with the NBC deal — the fusing of Stern’s and Ebersol’s shared vision, which brought the NBA away from its longtime partner CBS and into the multi-covered plumage of that glorious peacock.

“We crafted the offer — the final offer to CBS,” Stern explained shortly after the deal was completed. “We came up with what we thought was a deal that someone — who recognized our worth, our potential — would and should take. When CBS passed, we were not certain, but we were optimistic that somebody else would say yes.”

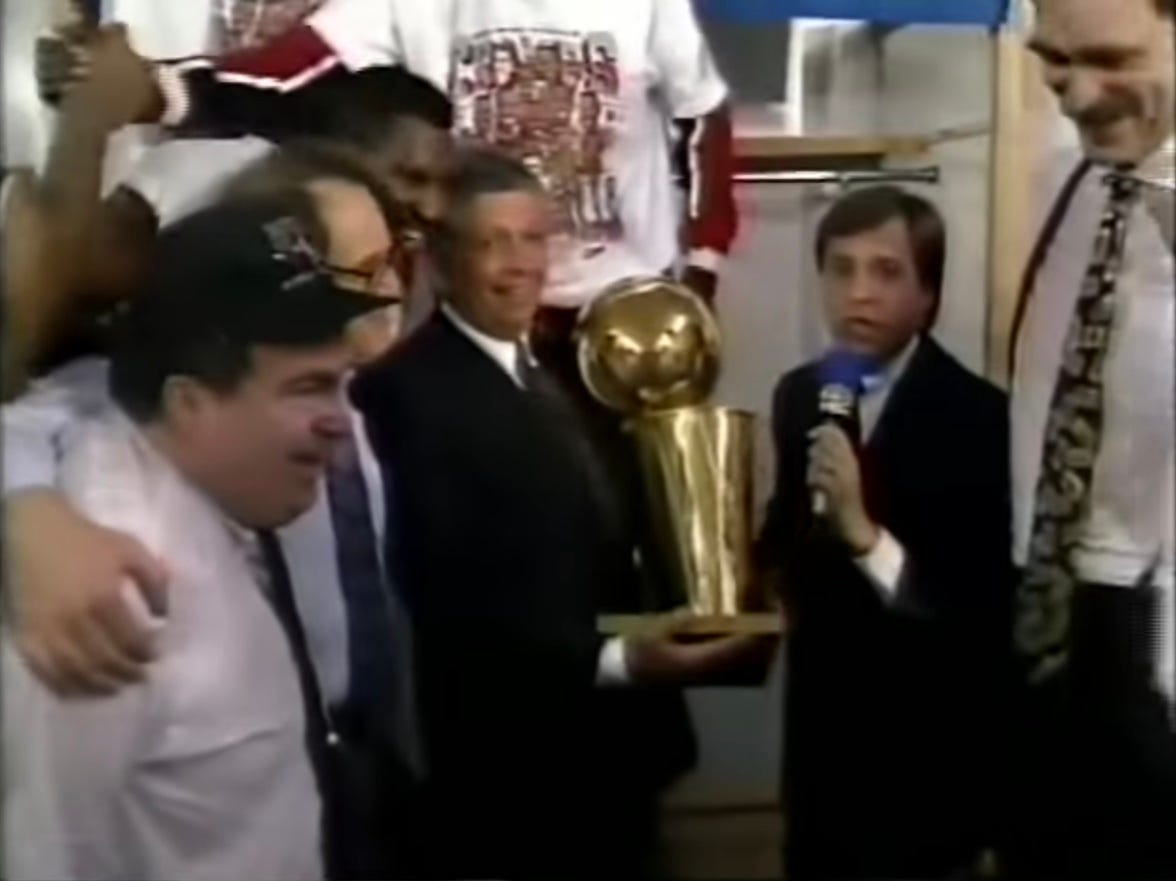

That somebody was NBC and Ebersol, who phoned Marv Albert at 7:45 a.m. the morning of the deal to tell him that he would have a role in the partnership. Albert became the voice of the NBA on NBC, captaining a happy little ship that was steering us all to basketball heaven. The broadcast team felt like a gang of friends having a party, and that party was an NBA game. There was Marv and his partner Mike Fratello, who Marv dubbed “The Czar of the Telestrator.” There was everyone’s main man Ahmad Rashad. There was Steve “Snapper” Jones. There was Hannah Storm. There were Jim Gray, Peter Vescey, and Matty Guokas. There was Bob Costas, who reported the harder news (no one made David Stern sweat more than Costas did in 1993, asking about Jordan’s gambling) and delivering some of the monologues (and eventually, taking over for Albert on play-by-play following the latter’s sexual assault charge in 1997).

With Marv at the helm, the NBA on NBC felt like a party unto itself, and we were all invited. On CBS, the NBA was a sport. On NBC, it was a happening. Stern wove the league into every fabric imaginable, and did so with an eye toward the future: the youth market. Stern tapped Rashad to host a program designed for children — “NBA Inside Stuff.” Starting with Game 4 of the ’91 Finals, Stern began shifting the NBA Finals from afternoon games to prime time broadcasts as “an opportunity to include all kids and family audiences.”

Under Stern’s watch, NBC debuted the cartoon series “ProStars,” in which cartoon versions of Michael Jordan, Bo Jackson and Wayne Gretzky are child-helping crime fighters. NBA Entertainment produced a library full of classic videos that got children hooked on the league and its personalities. All-Star Weekend became a celebration of youth culture, with the “Stay In School” campaign and other MTV-style bonanzas.

Central to it all, of course, was the basketball, and in the 1990s, the basketball reigned. Part of NBC’s mission in purchasing broadcast rights to the NBA was to replace what it lost a year earlier when CBS outbid everyone to gain rights to Major League Baseball. In 1987, the NBA Finals, in the third Finals matchup of Bird’s Celtics and Magic’s Lakers, set a new Finals ratings record at 15.9. That same year, the World Series on ABC drew a rating of 24.0. In 1988, when CBS bought its MLB deal while broadcasting the NBA, the NBA Finals drew a 15.4 rating with a game record high 21.2 for Game 7 between the Lakers and Pistons; over on NBC four months later, 13 million more fans watched the Dodgers drub Oakland in five games.

1990 was CBS’s final year with the Finals and first year with the World Series. The Pistons and Blazers drew 17 million viewers and a 12.3 rating, while 30.2 million viewers tuned in to watch the Reds sweep the As — a 20.8 rating. CBS appeared to have made the right decision.

Three years later, the NBA Finals reached a 17.9 rating with 27 million viewers, and a 20.3 rating for Game 6 as fans watched Jordan’s Bulls three-peat and knock off Charles Barkley. The equally thrilling World Series grabbed just 24.7 million viewers and a 19.1 rating for its own legendary Game 6.

It was the first time ever that the NBA Finals outdrew the World Series on TV.

“Oh! A spec-tac-ulah move — by Michael Jordan”

The 1991 NBA Finals were going to feel different no matter which two teams were there. Stern and Ebersol were making sure of that.

“Under Dick’s leadership, there was no property that was more important in our arsenal than the NBA, because we would have it exclusively,” NBC’s Jon Miller told Croatto. “So we put everything into it: our best talent, our best producers, our best directors, our best programming time, our best promotional windows, you name it.”

The two-time defending champion Pistons and the 1990 Finals runner-up Trail Blazers were back in the conference finals in 1991, and I’m sure that NBC would have gamely handled a rematch. The Celtics won 56 games in ’91 — a last dance of sorts for Magic and Bird would have been a glorious debut for NBC. Even getting Bulls-Blazers one year early would have been a win for the network and the league, considering Jordan’s popularity across from Clyde Drexler’s.

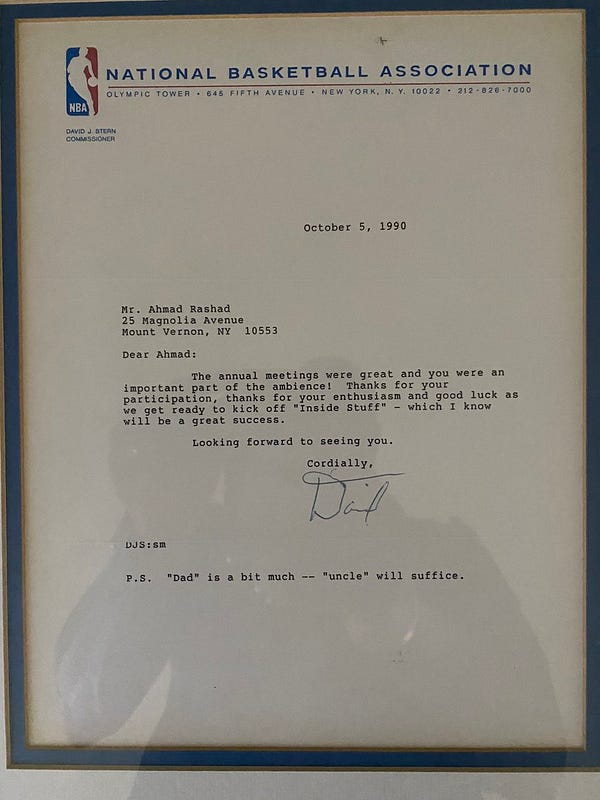

But for a network putting its best everything into the NBA, and a league entering a put-up-or-shut-up season, there was no better Finals matchup than the game’s two biggest stars: Michael Jordan and Magic Johnson.

“This is too good to be true — I believe it will live up to its billing and more,” said Orlando Magic president Pat Williams. “With slumping television ratings in all sports, this is a huge shot in the arm.”

NBC Sports Executive Producer Terry O’Neil called the Lakers-Bulls matchup a “pact with the devil,” noting that to that point, the playoffs had only two series go the distance, and they were both in the best-of-five first round. In the conference finals, the Lakers won in six but the Bulls swept the Pistons.

“If we were going to get the (ECF) sweep, we certainly at least wanted the marquee player in the game to survive,” O’Neil said just prior to the start of the Finals. “If someone had come and said to us, ‘You can have a seven-game series or Michael Jordan in the Finals,’ I think we might have chosen it this way.”

Well before the Bulls had secured the championship, the partnership between MJ’s play and NBC’s production was powerful. In a Game 2 Bulls blowout, Jordan delivered perhaps his signature career highlight: his famous switch-hands layup. And by “highlight,” I mean a play that would land on his highlight reel even without any additional context or game significance. This play was the essence of what Stern and Ebersol were building. You had the game’s biggest star on its biggest stage, captured by NBC’s expanded camera collection and called by Marv’s golden baritone.

MJ extended the ball toward the basket with his right hand, swooped it toward the middle of his body, took it with his left hand and laid it in off the glass while falling forward. We can all picture every beat of his jaw-dropping play. NBC cameras are a huge reason why. Croatto writes that while CBS used three to four replay sources for its games (a replay source is a camera designed for additional replays, particularly slow-motion, beyond what is broadcast live), NBC wanted to double that for the regular season alone.

The broadcast of the switch-hand layup started with the standard angle: a profile shot above the court. Replay angles then offered the following:

A court-level view from behind Jordan, over his right shoulder

A court-level view showing Jordan in profile from the right side

An elevated profile shot, over his left shoulder

A court-level view from the opposite end of the floor, showing the play from behind Jordan

There was also a sixth angle from under the basket, facing Jordan; in full, viewers had a 360-degree view of a play that is better appreciated at each degree. The play captured everyone’s imagination. On the playground, we practiced three types of plays: Magic’s no-look passes, Bill Cartwright’s rise-and-pause free throws and Jordan’s “spectacular move,” as Marv called it.

Everyone who wanted a piece of Jordan wanted that play, and it didn’t matter the angle. In August, eight weeks after the end of the Finals, Jordan’s most famous commercial (and that’s saying something) debuted: “Be Like Mike” for Gatorade, his new soft drink sponsor after his deal with Coke expired July 31, 1991. That commercial opened with The Layup as seen from court-level view from behind to the right.

“ProStars” debuted the next month, and the opening theme started with The Layup with the court-level profile angle from the right side. Three games after The Layup, Jordan, Pippen and the Bulls wrapped the Finals and won the franchise’s first NBA championship.

Best producers, best directors, best programming time, best promotional windows — best outcome.

A dynasty begins — two, actually

Elgin Baylor and Jerry West each lost their first seven Finals, including six together. Wilt lost his first. Isiah lost his first. Doc lost his first three in the NBA. (He won his first two in the ABA.) Kareem won his first, in his second season, but did not win again until his 11th. And while Magic and Bird each won their first two Finals, Magic lost his next two and Bird lost two of his next three.

This is all a long way of saying that Michael Jordan losing the 1991 NBA Finals would not have been the end of the world. Even if he lost the Finals in June of 1991, he likely would have still received his $18 million, 10-year deal with Quaker Oats / Gatorade in July. In September, he would have still been selected for the Dream Team. In October, the Bulls would have likely still been a top choice for national television games (entering the ’90-’91 season, they were 2nd with 16 total games, one behind Boston, and second for NBC games, tied with the Lakers and Celtics with 7, one behind the Pistons; games with the Bulls were the top 3 rated regular season games that year).

But the Lakers championship that many predicted (though not Sam Smith, who nailed it) would have made 1991 feel like a continuation of the 1980s. Instead, the Bulls’ resounding, five-game victory created a clear line of demarcation: a new champion for a new era. The viewers loved it. Despite the Bulls leading 3-1 and hence seemingly set for a championship, Game 5 of the 1991 Finals was the second highest rated Finals game since 1986, trailing only Game 7 of the ’88 Finals. Its 19.7 rating ranks 7th today, far ahead of more famous games that came afterward, including every subsequent Finals Game 7, those in 1994, 2005, 2010, 2013 and 2016.

The Bulls were every bit the ratings blessing the league and network hoped for. As reported by the Indianapolis News, the Bulls during the 1990-91 regular season improved NBC’s Neilsen ratings by half a point, while Bulls games on TNT — the league’s cable partner — were 13% above the league average.

That impact carried into the Finals. From 1986 to 1990, Game 1 of the NBA Finals averaged a 12.7 rating. From 1999 to 2019, it averaged 9.3. The six Finals with the Chicago Bulls had an average Game 1 rating of 15.6. Twelve of the 15 highest rated Finals games since 1986 featured Michael Jordan. The highest rated Finals ever was 1998, the final run of the Bulls, at an average viewership of 29 million fans per game, and just under 36 million for Game 6, the most fans to ever watch an NBA game.

The Bulls were both the best team and the best draw, and to what degree their continued success relied on one, the other or both is fair debate. Under David Stern, one never knew exactly how or when the NBA was seeking to manipulate results. The Tim Donaghy scandal brought evidence and court filings to Bird’s earlier suspicion of league bias. The bias was apparently so brazen that the league’s supervisor of officials Darrell Garretson even told the Bulls that when MJ committed fouls, the refs would if possible blow the whistle on one of his less heralded teammates, “because the fans don’t want to see Jordan foul out.”

No matter where you fall on the “David Stern manipulated league outcomes” spectrum, one thing is clear: the 1991 NBA Finals represented the official launch of a new era of NBA basketball. It was everything we, the basketball-loving fans, could have asked for, and everything David Stern could have ever wanted. Cue Roundball Rock. Cue Sirius. Cui bono.

-

-

-

I hope everyone is doing well! More to come, including two new interviews. Thanks a bunch to my guys Deremy Dove and Jose Ruiz and to Pete Croatto.

And happy anniversary to MJ’s 245th consecutive game after baseball: The Flu Game.