Dennis Rodman's gay 90s

My new Chicago Reader cover story on Rodman and Chicago's LGBTQ community.

“You also had LGBTQ bars on the south side. … Jeffery Pub may have been one of the oldest Black gay clubs not only in Chicago but in the United States. … Everything that people were doing, whether it’s the drag queens or the gay clubs, the gay businesses, entrepreneurs, creative people—I think all of that inspired Dennis to be as open and as bold as he was.”

— Chicago artist Otis Richardson on Chicago’s gay community’s influence on Dennis Rodman

Hi all! For anyone in Chicago, grab a copy of the Reader this week and check out my cover story on Dennis Rodman’s connection in the 90s to Chicago’s LGBTQ+ community: “Dennis Rodman’s gay 90s”.

I started thinking about this piece a few years ago, and it was cool to see it come together so quickly, starting last month when I pitched it. I had been slowly gathering material on the topic, not just on how Rodman immersed himself in gay culture, starting in San Antonio, but also how members of the LGBTQ+ community viewed him, some with wariness, many others with a full embrace.

One such person was illustrator Otis Richardson. In June of 1996, Otis was 32, living in Uptown and contributing art to the new magazine BLACKLines, part of Windy City Times. For the Pride issue of BLACKLines, Otis drew a pinup of a nearly nude Rodman with chain-connected nipple and naval rings. Twenty-four years later he tweeted his illustration during The Last Dance; I found it last year when dropping search terms into Twitter, looking for material about Rodman and Chicago’s gay community.

My research also yielded a 1997 story on Rodman from The Advocate, which put Rodman on the cover for their 1996 year-in-review issue, interviewing him about his gay sex fantasies and sex life, his childhood with regards to gender roles and cross-dressing and his overall views on sexuality in the 90s, and a San Francisco Chronicle story from June of 1996 where a writer watched a Bulls Finals game in a bar in San Francisco’s Castro district and asked patrons for their views on Rodman’s fluid sexual image.

The more I dug, the more I saw the story unfolding in front of me. My interviews with Otis Richardson and Chicago journalist and sports fan Parker Molloy were particularly insightful. Otis is a gay Black man, Parker a trans woman, and they both had illuminating views on what Rodman meant to them in the 90s. I’ll let you read the article for their quotes, and I’ll also be publishing their full interviews here at some point.

The biggest find — the one that really made me think I had a story here that I could do — was learning about writer and speaker Leslie Feinberg and her unusual choice with her 1996 book. Feinberg was a leading thinker on LGBTQ+ issues, helping define language in the queer community, and in 1996 she published Transgender Warriors: Making History from Joan of Arc to RuPaul.

What was unusual about that? Well, months after her book came out, as she was working on the paperback release, she became so enamored by Dennis Rodman that she changed “RuPaul” to “Dennis Rodman” and wrote an entire afterword about his impact. I particularly like these passages:

In writing this story, I learned that Chicago is considered by some to have the country’s first gay rights group (in 1924) and first Pride Parade (1970), and that in 1997, Chicago became the first city in the country to designate a gay district with Northalsted. That happened while Rodman was on the Bulls, and while it certainly did not happen because of Rodman, it is an important backdrop to why Rodman felt so at home here. The Bulls had a huge part in his comfort, but Chicago did too.

And still I returned to Feinberg, reading her afterword and other passages of her book, and watching several interviews with her, including this one from October of 1996 where she explained again why she changed her subtitle to honor Rodman (start at the 15:11 mark):

Even more striking to me was a presentation she gave in 2008, explaining the connection between the struggles of undocumented workers and those of trans people, a distressingly relevant topic today. Here’s how she set the stage for her speech:

“I came out in the gay bars which were also drag bars. We didn’t have the word ‘transgender’ then but we also didn’t have the word ‘gay’ then. All the words that we had were words that got hurled out of a car window (that) got rolled down and you knew there was a full beer can coming after it, or worse. When I came out into those bars I never could have imagined in a life that I was leading where it was so isolated, where the terror of just getting from home to my job in the factory or from home to get a quart of milk or to be out in public was such a dangerous thing to do. And why? Because I was masculine-female. … These were things I had to know. This was my life, and anybody could take it from me at any time, by any stranger. … I had to know why…”

Reading Feinberg, and listening to her, I could understand why Dennis Rodman’s gender expression and embrace of people in the LGBTQ+ community meant so much to her. I understood her bond with him. I felt a similar bond in the 90s but with much lower stakes. I liked Rodman because he was creative and original and enthusiastic and an outsider, and I viewed myself to varying degrees as all of those things.

But he meant much more to Feinberg, and to Parker, and to Otis, and I recalled the huge impact that Phil Taylor’s great 1996 Rodman rebounding feature in S.I. had made on me, when Taylor reported that Rodman was watching film in the Miami Heat visiting locker room in a t-shirt that said “I DON’T MIND STRAIGHT PEOPLE, AS LONG AS THEY ACT GAY IN PUBLIC.”

More than seeing Rodman in drag on the cover of S.I. the year before, more than seeing him at either of his two 1996 book signings in drag, it was that scene in that article that clicked with me at 14 years old. I immediately understood something that I had never articulated, the notion of how one identity is “normal” and another is not, how saying straight people should act gay in public was no more or less legitimate than the very common opposite.

Perhaps just as valuable as Rodman influencing the national conversation around sexuality and gender was his embrace of gay people and his refusal to throw them under the bus. In the same era as Magic Johnson and Isiah Thomas’s friendship splintering in part over Isiah wondering if Magic contracted HIV due to gay sex, and basically the same era (2002) as Mike Piazza holding a press conference to announce that he was not gay, Rodman was confident enough in himself to regularly answer questions about his sexuality by saying that while, no, he wasn’t gay, that’s just because he wasn’t, and if he one day decided to be with a man, he would do it.

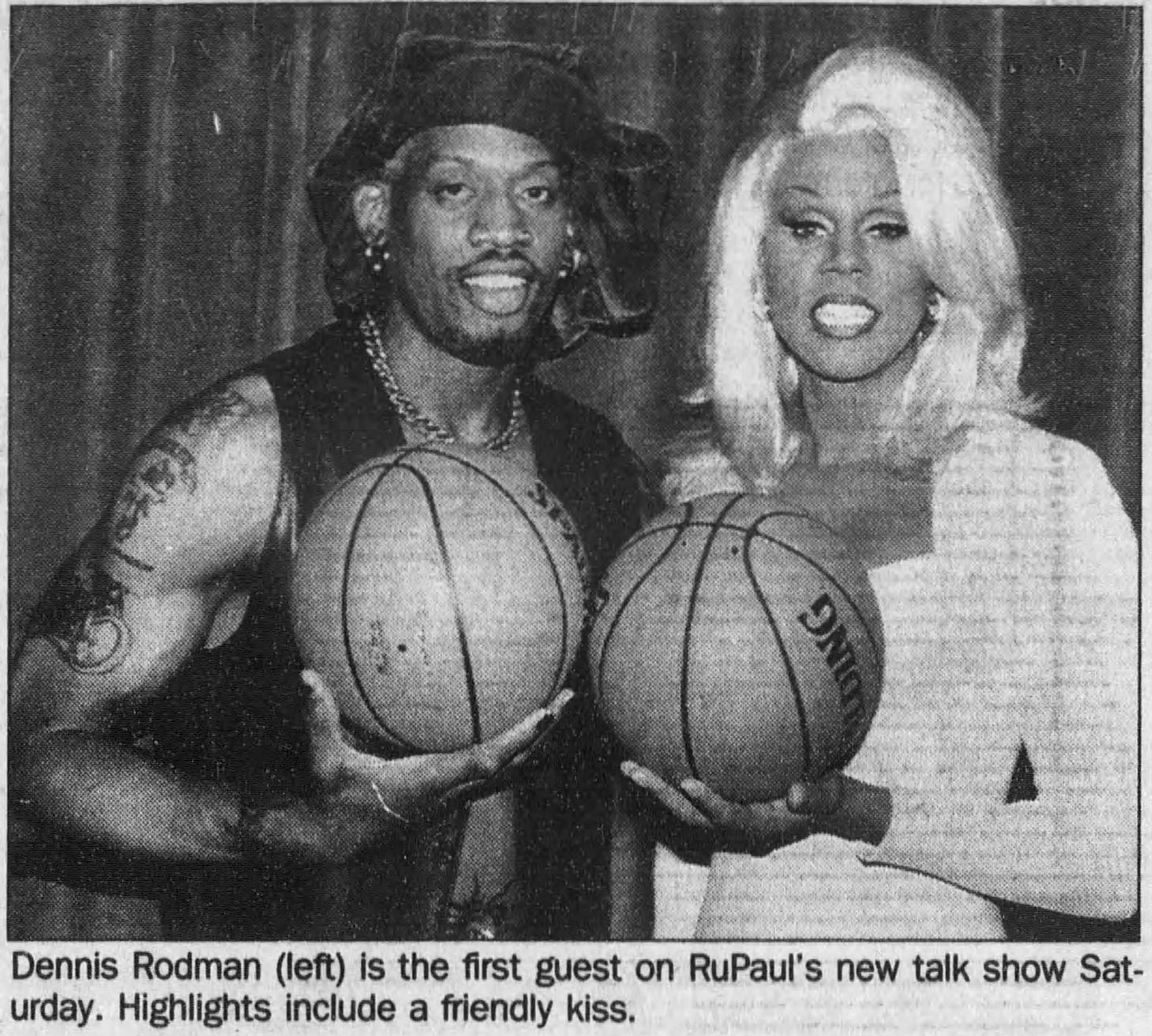

When RuPaul launched The RuPaul Show in 1996 and had Rodman as his first guest, he asked Rodman if he would kiss him on air. Rodman shrugged and did it.

I don’t know that anyone can ever be a “perfect” ally, and Rodman in the 90s was far from the perfect ally. As patrons in the Castro gay bar told the Chronicle writer, or as some readers of the Advocate story expressed, Rodman’s personality ran the risk of making queer people seem more like outsiders, not less.

“If an athlete is going to make it easier for a gay person to come out, he’d have to be very straightforward, a Cal Ripken-type,” one of the Castro bar patrons said. “More people would be able to identify with him. Rodman is too bizarre. If someone’s an oddball, he’s an oddball, whether he’s gay or straight.”

Yet after listening to his friends at the bar arguing on behalf of Rodman’s impact, the man conceded a point.

“What Dennis Rodman has done is raise the issue,” he said. “I guess that in itself is valuable.”

Thanks for reading everyone! Thank you to Salem at the Reader for making this story happen. Thank you to Otis, and thank you to Parker for her friendship and fabulous journalism. She’s a fellow 90s Bulls nut, a great baseball fan and one of the best media critics working today. Make sure you check out her work: